By now, all horror fans worth their salt are aware of the tropes that horror films use. Wes Craven’s 1996 film Scream was one of the first horror films that dissected the tropes as they were happening, showing us the rules to horror movies as they played out on screen. We all should have a firm grasp of horror tropes now. The killer is never dead at the end, no matter how charred his body is, or how riddled with bullets he seems. Taking your clothes off for any reason is a bad idea. The person who says, “I’ll be back in a minute,” will never return. Never for any reason go into the basement when the killer cuts the power lines. Basic stuff.

The rules satirized in Scream also helped define the Final Girl in horror films. Bad girls who drank, did drugs and had sex were going to be killed first, leaving the sober and sexually virtuous good girl as the “final girl” who faces down evil and destroys it (until the killer is resurrected for the sequel). Scream subverted that rule, as Sidney, the final girl, loses her virginity right before she is tasked with eliminating the two doofuses who have been terrorizing and killing people.

Final girls have always played a part in horror films that focus on killers. Their roles are almost instinctual, primal, repeating the same pattern of behavior regardless of the film or the director. Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre gave us blonde, brave but terrified Sally, who escaped when everyone else fell to Leatherface. She didn’t kill the cannibals but she managed to get away, definitely a final girl. Nancy from A Nightmare on Elm Street, Laurie from Halloween, Alice from the first Friday the 13th, Sarah from Descent, and, of course, Sidney from Scream all embody the sort of purity combined with intelligence that permitted them to survive at the end.

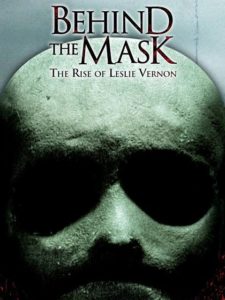

There are too many examples of this trope to list them all, and there have been a lot of self-aware films like Scream or Cabin in the Woods where the Final Girl trope is explored, but none are as good, in my opinion as Behind the Mask: The Rise of Leslie Vernon, a terribly underrated mockumentary and black comedy about an aspiring serial killer and his preparation for his first real rampage. All the serial killer tropes are laid out, alongside self-referential takes on how much cardio a killer must engage in to be able to track down running victims, the ridiculous desire for victims to clump together, the equally bizarre tendency for fleeing victims to trip and fall on level ground, and similar rules. But the best bit of meta in this film is the “final girl” trope, which is called the “survivor girl.”

There are too many examples of this trope to list them all, and there have been a lot of self-aware films like Scream or Cabin in the Woods where the Final Girl trope is explored, but none are as good, in my opinion as Behind the Mask: The Rise of Leslie Vernon, a terribly underrated mockumentary and black comedy about an aspiring serial killer and his preparation for his first real rampage. All the serial killer tropes are laid out, alongside self-referential takes on how much cardio a killer must engage in to be able to track down running victims, the ridiculous desire for victims to clump together, the equally bizarre tendency for fleeing victims to trip and fall on level ground, and similar rules. But the best bit of meta in this film is the “final girl” trope, which is called the “survivor girl.”

Right about here you may want to stop reading if you have yet to see this film because there will be spoilers.

A quick summary is in order: Taylor, an aspiring film maker arrives in a small town in Maryland with her two member crew to record the preparation of one Leslie Vernon, an ostensibly abused boy with a miserable back story, for his return to the town that spurned him to exact revenge on as many teens as he can. Leslie and Taylor have a weird  chemistry that becomes more obvious as the film goes on, as Leslie introduces Taylor and the crew to his serial killing mentor, played by the superb late Scott Walker, and discusses all the cliches and tropes Leslie engages in and uses in his preparation for his rampage. Leslie has ostensibly selected a virginal blonde named Kelly to be his “survivor girl,” and he intends to descend on Kelly and her friends as they hang out in the old Vernon home to get stoned and party. Taylor and her film crew decide they can’t let Leslie kill the teens and Taylor engages in a final showdown with Leslie. The film also features the late Zelda Rubenstein as a librarian and Robert Englund, Freddy Krueger to you and me, as Leslie Vernon’s psychiatrist. His role harks back to Donald Pleasence as Dr. Loomis in Halloween, and he clearly had a great time chewing the scenery in every shot he was in.

chemistry that becomes more obvious as the film goes on, as Leslie introduces Taylor and the crew to his serial killing mentor, played by the superb late Scott Walker, and discusses all the cliches and tropes Leslie engages in and uses in his preparation for his rampage. Leslie has ostensibly selected a virginal blonde named Kelly to be his “survivor girl,” and he intends to descend on Kelly and her friends as they hang out in the old Vernon home to get stoned and party. Taylor and her film crew decide they can’t let Leslie kill the teens and Taylor engages in a final showdown with Leslie. The film also features the late Zelda Rubenstein as a librarian and Robert Englund, Freddy Krueger to you and me, as Leslie Vernon’s psychiatrist. His role harks back to Donald Pleasence as Dr. Loomis in Halloween, and he clearly had a great time chewing the scenery in every shot he was in.

The relationship between Taylor and Leslie is the most interesting part of this film. Leslie is training to become a legendary serial killer like Jason Voorhees or Michael Myers, and initially Taylor is enthusiastic, if not a little squeamish, to document Leslie’s preparation. Initially they seem to have an openly symbiotic relationship – she gets to make a (hopefully) well-received documentary and he gets to enjoy the fame and notoriety such a documentary will give him. But Taylor’s humanity rises up, almost predictably, and if I can predict it, that means that Leslie did as well. Taylor discovers that Kelly was not really ever meant to be the “survivor” girl, and that Leslie’s plans for mayhem were far more carefully laid out and prepared for than she could have imagined.

In one scene, Leslie discusses the sexual elements of the serial killer versus victim interactions. Killers seldom pull characters out of closets and kill them because closets symbolize a sacred safety in the womb. Final girls almost never use guns because part of the credo demands the girls find and use a phallic-like object to kill their attacker. And since those survivor or final girls are supposed to be virtuous virgins, by using a phallic object to kill an attacker, they are symbolically becoming women while changing roles with the male killer as the penetrator. Leslie wants his survivor girl to be worth all the effort he has put into his plans, especially since his mentor ended up marrying his final girl, and he cleverly sets up Taylor to play a far more hands-on role in his rampage.

As absorbed in the meta as this film is, the interesting connection between Taylor and Leslie gives this film an interesting tension that plays well alongside the humor in the film. Leslie Vernon is intense but he also has a jocular sense of humor, and Taylor’s flustered attempts to control what is happening are outright funny as she cannot help but engage in the exact tropes Leslie has explained to her. In one especially funny scene, Leslie forces Taylor and her crew to leave the house where the teens are partying because he says she has a look on her face. What look, you may ask. “The we can’t just stand here and let this happen look.” Later, when Taylor tries to convince her crew to help her stop the massacre, she utters that exact phrase, which her crew points out is exactly what Leslie said when he threw them out. Later, Taylor realizes Kelly was never meant to be the final girl. Taylor, virginal and nervous, is the final girl, and far from it being a terrible betrayal, it’s clear Leslie made his selection because Taylor was the best possible foil.

This film is notable to me because of the very real relationship shown between the final girl and the killer. No long-lost sister, no revenge motive. Just a girl selected specifically by the killer because he knows she is the perfect woman to play the role of the final girl, seeing in her the capacity for survival that she would never have seen in herself. It’s a strangely touching conceit, to create such a bond between killer and final girl, one that is not tainted at the end like Sidney Prescott’s bond with the killers in Scream. The killers in Scream hated Sidney and wanted revenge on her for her mother’s own promiscuous behaviors that broke up families, but they never selected her believing that she could potentially defeat them. The motive was revenge, pure and simple (and also because they were psychopaths…). Leslie’s choice for his final girl is far more personal and, strangely, egalitarian. He picks his final girl because he knows she could defeat him.

If you are a fan of horror movies and you have not seen this film, go and watch it. Even though I spoiled it, there is a lot – a lot – I have not touched on. It’s a funny, violent, creepy and unexpected gem of a film. Check in tomorrow for more on the Final Girl trope.