Book: The Ghosts of My Friends

Creator: Cecil Henland

Type of Book: Autograph book, novelty

Why Do I Consider This Book Odd: Because it’s just such an interesting intersection between sentimentality, Rorschach’s test, and the turn of the century interest in klecksography.

Availability: This is a vintage book. I cannot seem to find the date this book was published but the earliest signed signature in my copy is in December, 1907. There were two editions from London and New York. The copy I bought from a rare book shop on Abe Books, is a London edition, published by Dow & Lester, and at this moment there is no genuinely vintage edition of this book from either printing for sale on any of my go-to shops for interesting books.

Comments: I have been doing a lot of genealogy research lately and have been beating my head against a wall where one branch of my family tree is concerned. I simply cannot find proof that the man who may be one of my seventh great-grandfathers had a son with the name of one of my actual sixth great-grandfathers. It is unlikely this research block will be solved by DNA testing yet I spat in a tube for half an hour and mailed it off anyway. I’ve also been cleaning up and reorganizing some bookcases and came across my copy of this delightful little book. I sat down for a moment to flip through it and look at the little ink blot signatures and with several ancestry research sites open on my computer, I decided to plug in the names because it seemed like a reasonable thing to do at the time.

Comments: I have been doing a lot of genealogy research lately and have been beating my head against a wall where one branch of my family tree is concerned. I simply cannot find proof that the man who may be one of my seventh great-grandfathers had a son with the name of one of my actual sixth great-grandfathers. It is unlikely this research block will be solved by DNA testing yet I spat in a tube for half an hour and mailed it off anyway. I’ve also been cleaning up and reorganizing some bookcases and came across my copy of this delightful little book. I sat down for a moment to flip through it and look at the little ink blot signatures and with several ancestry research sites open on my computer, I decided to plug in the names because it seemed like a reasonable thing to do at the time.

I didn’t discover that a famous or notorious person signed this copy of The Ghost of My Friends but the amount of time I spent looking into the people who signed and the history of the book, I realized I should probably write about it.

The signatures in this book may initially bring to mind the Rorschach ink blots used to make personality determinations based on what it is people see when they view a symmetric, but otherwise random image. However, for the purposes of this discussion I think it’s best to look at the 19th and early 20th century fads around ink blots, and this decision has everything to do with the fact that I have spent far too much time lately investigating the administration of the Rorschach test to be able to speak about it in under five thousand words or so.* There was a surprising amount of interest in seeing images in ink blots prior to the creation of the Rorschach test in the 1920s, and while those fads certainly influenced Rorschach, they are interesting in and of themselves.

One such example was the work of a poet called Justinus Kerner, who was also a medical doctor, entry-level occultist and first identified botulism (people had a lot more free time back then because there was no Twitter). Due to failing eyesight, Kerner often marred his paper with ink blots, and one day, after examining some of the crumpled pieces he thought were ruined, he noted that when folded in half the ink made an interesting pattern. He decided to make more ink blot art and used those patterns to illustrate a book of poetry called Kleksographien, which you can and should look through in its entirety, and it is believed that Rorschach had access to the book. The title, translated into English, is “klecksography” and that literally means “making ink blots.”

Klecksography became a popular pastime for children during the late 1800s. I found references on Wikipedia and across various blogs to one klecksographic game called Gobolinks or Shadow-Pictures For Young And Old, which amazingly has been reprinted. You can also thumb through the original version on Project Gutenberg. The game encouraged children to make monsters out of ink blots, which in turn were used to stimulate their imagination by creating stories about those monsters, the so-called “gobolinks.” This book is a descendant of such games, rather than a tool meant to genuinely analyze behavior or personality.

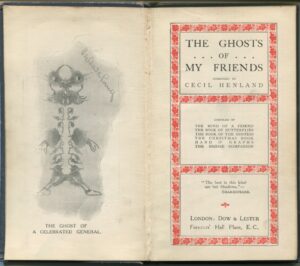

The Ghosts of My Friends was the creation of Cecil Henland, and I can find very little out about her life. In fact, I found out more concrete information about her husband than I did about her. The most I could come up with about her was from a message board devoted to fountain pens. User cercamons discovered that Cecil was a woman, something that is good to know before one writes a long article making assumptions about the implied gender of the name “Cecil.” Cercamons discovered that Cecil was a “founder of a nursery school system in England and the widow of Lt. Col. Arthur Jex-Blake Percival, who was killed in battle in November 1914.” Click on the image for the larger version to see all the very interesting books Cecil Henland created, including Hand of Graphs. I can find out nothing about Hand of Graphs yet I somehow know I want this book very badly.

The Ghosts of My Friends was the creation of Cecil Henland, and I can find very little out about her life. In fact, I found out more concrete information about her husband than I did about her. The most I could come up with about her was from a message board devoted to fountain pens. User cercamons discovered that Cecil was a woman, something that is good to know before one writes a long article making assumptions about the implied gender of the name “Cecil.” Cercamons discovered that Cecil was a “founder of a nursery school system in England and the widow of Lt. Col. Arthur Jex-Blake Percival, who was killed in battle in November 1914.” Click on the image for the larger version to see all the very interesting books Cecil Henland created, including Hand of Graphs. I can find out nothing about Hand of Graphs yet I somehow know I want this book very badly.

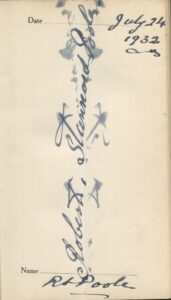

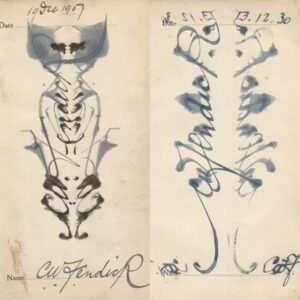

The first page offers some useful instructions and it’s interesting to note that later entries are less distinct than earlier ones, lacking the smudging and theatricality of earlier blots. I lack the will to determine if fountain pen technology improved from the 1900s through the 1930s but one presumes that it did. Perhaps the parts of the pen that control how the ink funneled down into the nib became more refined. Regardless, anything that improved ink flow and prevented ink from spotting the page affected the drama of ink blot ghosties. You can see this play out in one of the ghosts from 1932. Not enough ink leaked out to leave a proper image on both sides when the paper was folded.

Now for the ghosts!

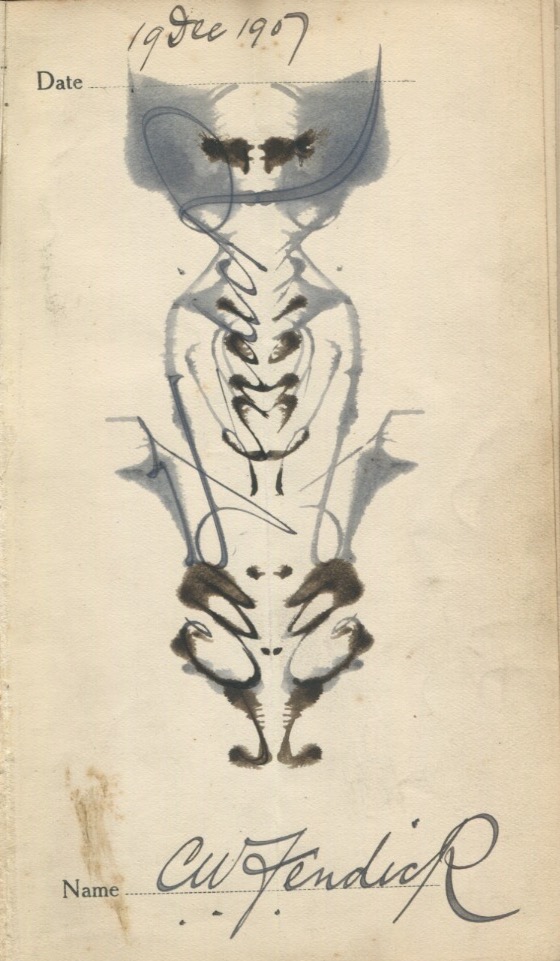

The first page is signed by C.W. Fendick on December 1907. Because Ancestry.com exists, I easily tracked down the Fendick family in a 1911 census record. This is the pater familias, one Charles William Fendick. He was 42 or 43 when he signed this. He was married to a woman named Selina, and in 1911 they had five children: Margaret Selina, Charles Percy, Edith Helen Alice, Sidney Walter, and Reginald Stanley. I’m glad people printed their names but I also wish I could unsee the printed name until I tried to decipher the signature. But when the printed name is illegible, it’s just as bad because most of the time I need the printed name to discern the name in the signature ghost. So there you go.

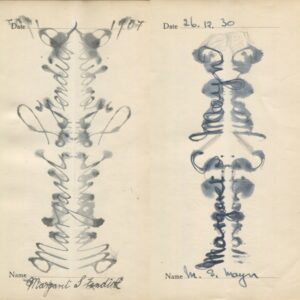

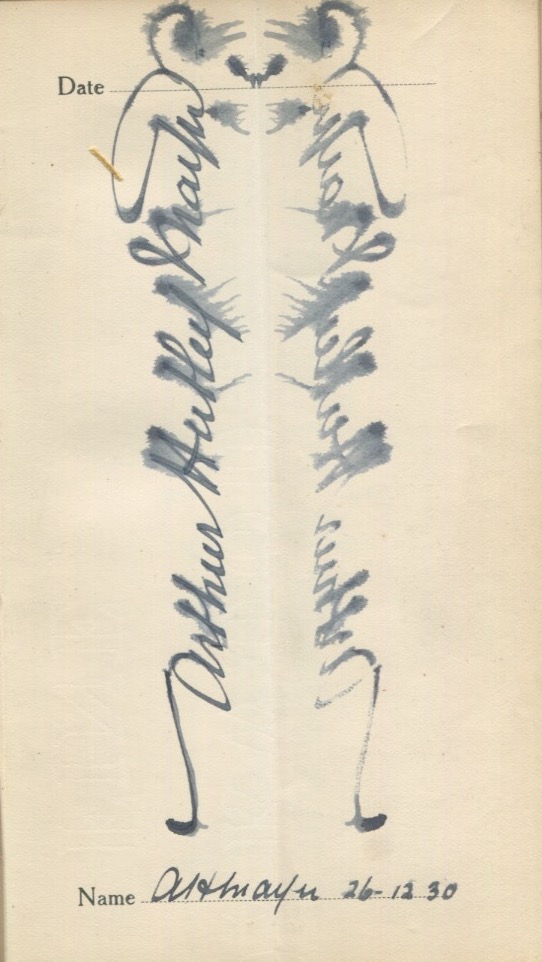

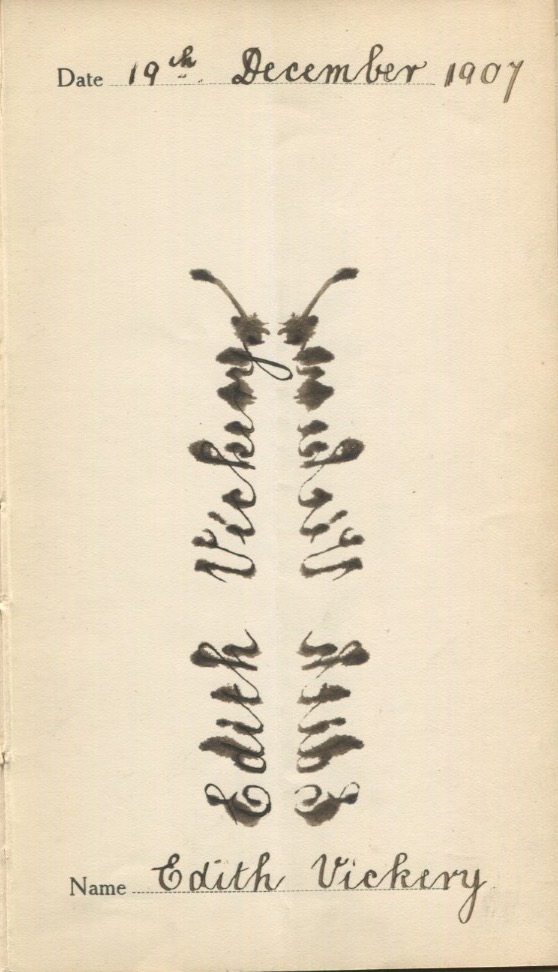

Were I to hazard a guess, I would say this book belonged to Margaret Selina Fendick. There is no inscription to prove this, but later in the book, on December 26, 1930, we see the ghost of a man named Arthur Mayn. Margaret married an Arthur Mayn on October 20, 1923. It looks like this little book was signed mostly around the holidays. I can’t help but think that Margaret was reminded of this book around the holidays in 1930 – her father, mother and brother Sidney signed it again on December 12, 1930 – and she signed it with her married name and got her husband to sign it, too. Margaret Selina would have been 15 or 16 years old during the first volley of signatures. It seems like this novelty book would have been a fun gift for a teen girl. Something else that lends credence to the idea that this book belonged to Margaret Selina is that one of the first signatures in the book belongs to “Edith Vickery.” I found an Edith Vickery in Essex who would have been about 14 or 15 years old when she signed, making her the right age to be a school friend of Margaret’s. Other surnames appeared in the book as well, like Poole and Cooper, but I did not research them because at some point even I know when I have gone on far too long.

The book is fairly fragile so we did not scan every autograph in the book. We grabbed the “ghosts” who seemed most interesting to us. I’m including my two favorites in a larger size but you can click on any image to get a closer look.

If you don’t see a teddy bear peeking up at you over the top of the signature, can we even be friends?

If you don’t see a teddy bear peeking up at you over the top of the signature, can we even be friends?

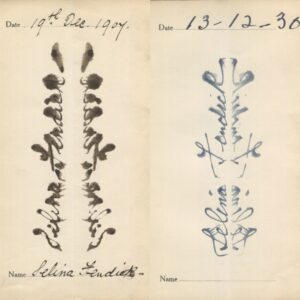

One cannot help but feel that within young Edith Vickery was a butterfly waiting to burst forth from this adorable caterpillar.

One cannot help but feel that within young Edith Vickery was a butterfly waiting to burst forth from this adorable caterpillar.

One thing I really found interesting in this book was that people re-signed the book, often with over two decades between signatures. That means we can see how the “ghost” changed over time. I’m including examples from Margaret’s parents, CW Fendick and Selina Fendick, as well as Margaret herself.

Today’s entry has been brought to you by enormous AI-generated ancestry databases and late Victorian fountain pens. I wish I had more reason to write with pen and ink. If I tried to do an ink blot ghost signature, it would likely look like a large A followed by random squiggles, and the only ghost one would see would be that of my muscle memory for handwriting. Though this book cost far more than was likely reasonable, I’m glad I grabbed the copy when I saw it. I don’t think I know how quickly time is passing and the recent past becoming relic until I stumble across books like these.

*I have been researching Rorschach tests because of the work I am still doing on my book about failed assassin, Arthur Bremer. I am indeed still working on the book, I suspect I will always be working on the book in some manner, but hope the actual work anyone would be interested in reading will come to an end this year. Arthur played hilarious games with earnest psychiatrists who asked him to describe what he saw in ink blots. Yeah, he shot four people and was sort of a proto-but-largely-benign-incel, but his therapeutic chicanery made me feel very fondly toward him.