Book: The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Deaths

Author: Corinne May Botz

Why I Consider This Book Odd: The book documents unexplained deaths as depicted in the form of miniature, almost dollhouse-like scenes. This book is bizarre, creepy yet utterly charming.

Type of Work: Photography, essay

Availability: Published by Monacelli in 2004, you can get a copy here.

Availability: Published by Monacelli in 2004, you can get a copy here.

Comments: I discussed this book fifteen years ago, back when this site was still I Read Odd Books. I had been thinking about reposting the discussion because it’s such a great book and having posted it so early in my book blogging “career,” it seems worth reposting it because few current readers have likely seen it. Add to that that Corrine May Botz is giving a talk on December 8, 2024 for Morbid Anatomy and this seems like a perfect time to repost this extremely cool book that covers the work of a decidedly odd, very gifted woman. What follows is more or less an unaltered repost, though I’ve rejiggered parts of it to conform to the way I now handle quotes and photos.

This book is amazing. Though the content is likely a bit morbid for most to consider it a coffee table book, had I coffee table, it would definitely be prominently displayed on mine. The book discusses the career of Frances Glessner Lee, a woman Corinne May Botz describes as:

“…brilliant, witty , and, by some accounts, impossible woman. She gave you what she thought you should have, rather than what you might actually want. She had a wonderful sense of humor about everything and everyone, excluding herself. The police adored and regarded her as their “patron saint,” her family was more reticent about applauding her and her hired help was “scared to death of her.”

Raised in an ultra-traditional, very wealthy family, Lee spent a good majority of her young life thwarted, though she was exposed to home decorating skills that would stand her in good stead when she began making the Nutshell Studies. Unable to attend college as she wanted, once her parents died, Lee started to come into her own, both metaphorically and literally, as she then had plenty of wealth to support her interests. She met a man by the name of George Magrath, a medical examiner who testified in criminal cases in New England. Magrath enthralled the young Lee, and it was through Magrath and his knowledge that Lee began to see what would become her life work.

Interested in promoting proper examination techniques to coroners, who were then mostly untrained in criminal investigation, she founded a library at Harvard (where her parents had refused to allow her to study) that contained over a thousand rare books she had collected. With her inherited wealth, Lee set up the George Burgess Magrath Endowment of Legal Medicine, and though she did not have any formal training, she was respected as an authority in what would later become forensic sciences.

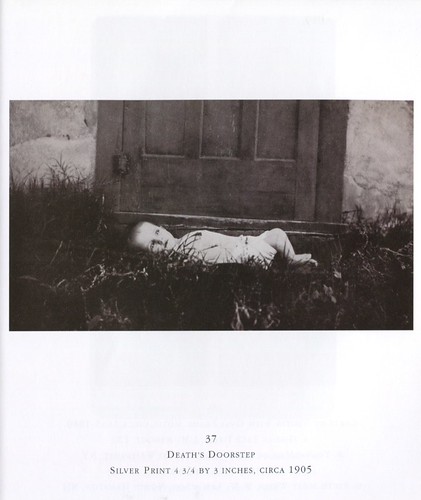

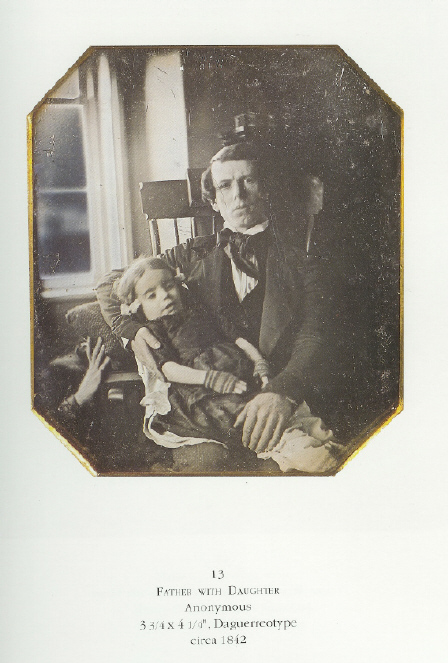

However, it did not go unnoticed to Lee that students could seldom get any hands-on training, due to many factors, the main one being that few crime scenes of interest occurred when students were in training sessions. That caused her to create the Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death. These death scenes in miniature were physical reenactments of baffling cases, set up meticulously so that students could study them and analyze the clues and evidence in the scene, and come to an appropriate conclusion. Some were suicides that looked like murders, accidents that looked like suicides and some were murders that the killers tried to make look like either suicides or murders. The goal was to encourage students to study and find all pertinent information the scenes provided. She held seminars using her miniature scenes as visual aids. She made it clear that it was not always necessary to find the cause of death, but rather the scenes were “exercises in observing and evaluating indirect evidence, especially that which may have medical evidence.”

The sheer amount of work that went into the Nutshell Studies, as well as Lee’s incredible attention to detail, astonishes me. All of her skills and knowledge were poured into the miniature scenes. Working from crime scene photographs, she would construct detailed scenes, filled with information – some relevant, some not. The models she created worked, in the sense that one could raise the blinds, a tiny mousetrap would spring, and the coffee pots were filled with coffee grounds. With her knowledge of interior design, Lee selected wallpaper and furnishings that matched the socio-economic and class structure of the victims in the studies. She agonized over the scale of everything, making endless adjustments until the entire scene was in perfect scale.

No less attention went into the dolls, representations of dead people. Stuffed carefully to ensure flexibility, clothing hand made (even down to Lee hand knitting silk stockings for the dolls), and posed with care, these dolls became macabre representations of terrible ends. Though Lee never felt as if her dolls looked realistic enough, she had no qualms about creating dolls that showed the extremes of violence and death.

Though Botz observes this in decidedly more eloquent prose, as I read the essay about Frances Glessner Lee, I could not help but think that her choice of life work was a huge middle finger extended towards her parents and society as a whole. Her parents refused to let her get a college education and taught her that she “shouldn’t know anything about the human body.” Yet she ended up in a career where she attended autopsies and created representations of terrible crime scenes. Better yet, her career brought her into close proximity with lots of attractive, unmarried young men, a situation that had to be satisfying to her even though most of them saw her as a maternal figure, sending her Mother’s Day cards. Once her parents were dead, Lee did not set back the clock and get the education she wanted, but rather used her inheritance to become involved in legal medicine, a subject of which her father heartily disapproved. Though some of her class prejudices showed up in her works – she was reluctant to show crime in upper class settings – her quiet assumption of a decidedly unfeminine career, as girlie as making dollhouse scenes may be, was a blow for her personal freedom as well as a chance to do that which interested her.

The book is primarily made up of photographs and information about the scenes Lee created. Each scene collection has a numbered picture at the end that shows all the various clues and information one should have gleaned from the scenes, as well as analysis of what one could potentially think of the information. For some of the scenes, at the end of the book isa sort of answer key, so one can see if what one saw in the scene had any relevance to a crime. It’s an interesting diversion for those of us interested in the macabre, looking at these scenes and trying to puzzle out what Lee wanted us to see, absorb and interpret.