It has been far too long since I have discussed Chris Mikul on this site. When I decided to devote a bit of Oddtober to media for children, I remembered that Mikul had released a Biblio-Curiosa devoted to kid’s books and the authors of said books. As is the case with just about everything Mikul writes, I could write reactions to his articles that are longer than the articles themselves but I will work to restrain myself. In the past, Chris Mikul sent me down a fascinating rabbit hole chasing the memory of the man known as F. Gwynplaine MacIntyre, as well as discussing the book that has since become my odd book Holy Grail, The Pepsi-Cola Addict by the surviving Gibbon twin, June, a name likely known more to fans of strange phenomena than to bibliophiles.

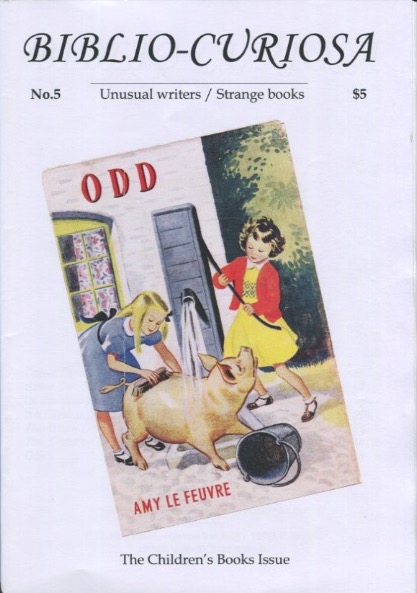

His body of work is what I’ve often said I hope OTC can be when it grows up, which it probably won’t. Which is just as well because Mikul’s work approaches being sui generis, and it’s a bad idea to mimic that which is one of a kind, though it’s always nice to have such inspiration. Issue 5 isn’t creepy or Halloween-y in a supernatural way, but all the books he discusses in this issue have some element to them that is strange, eerie or odd. Emphasis on “odd” because, as the title reveals, one the books he covers is actually entitled Odd.

The fact that the cover is re-enacted in my neighbor’s backyard in no way influenced me where Mikul’s look into this book is concerned. It should also not be surprising that I would be kindly disposed toward a book that features two little girls washing a pig.

The fact that the cover is re-enacted in my neighbor’s backyard in no way influenced me where Mikul’s look into this book is concerned. It should also not be surprising that I would be kindly disposed toward a book that features two little girls washing a pig.

This was one of the shorter of the seven articles in this edition, but it struck me as being the most relevant to my interests and as being the story that best illustrates one of the many paths a child can take to becoming an odd adult. Odd tells the story of six-year-old Betty, daughter of an MP and the middle child of five. Her two elder siblings are close in age and her two younger siblings are twins, leaving Betty on her own. She is literally the odd one out. One day Betty accidentally knocks one of her younger brothers down and is locked in a storage room with a Bible (!!) as punishment. Her nanny tells her she cannot come out until she memorizes a Bible passage. And it’s here that the “weird kid” roots begin to take hold. Mikul describes the scene:

Turning its pages, Betty comes to the Book of Revelation and the text “And I came unto him, Sir thou knowest. And he said to me, These are they which came out of great tribulation, and have washed their robes, and made them white in the blood of the lamb.” Betty learns the text by heart and becomes obsessed by it. She finds out what tribulation means, and after that asks everyone she meets if they have experienced it yet. She is terribly worried that tribulation is only for grown-ups, and if she dies before experiencing it she won’t go to heaven.

This resonated with me strongly. As a child who grew up in a large city in the American South, I cannot be the only kid who, when confronted with another child’s steadfast opinions regarding baptism and salvation, became convinced that I was going to hell because Southern Baptists didn’t baptize babies (or at least my church didn’t). Luckily I was able to ignore conversations about full body immersion versus top of head christenings and avoid a freakout because I figured that even if the top-of-headers were correct, the top of head got wet in a full body immersion so pretty much everyone would be fine in the end.

So the middle and odd kid’s parents have to go away and in what I feel like is a typically upper-class British manner, the kids are sent to live for six months on a farm their nanny’s brother owns, and are permitted to run amok unsupervised in manner that would likely make the evening news if it happened in my neck of the woods. Betty meets all sorts of grownups, including a church organist, who gives Betty a puppy, which predictably causes Betty to worry about whether or not her dog will go to heaven. Betty develops a friendship with the father of a dead little girl, and genuinely enjoys the company of adults, and in turn the adults in her life don’t mince words or treat her like a foolish little child. They don’t speak to her like an equal, but they also do not shelter her and as a result she takes the slings and arrows of life with more equanimity than many modern adults would. The book ends with a tribulation that involves a mad dog and sacrifice and if this sounds familiar know that Amy le Feuvre’s Odd was published in 1897 and that she handled the way such a plot plays out far better.

In this issue, Mikul also shares the story of E.W. Cole and his astonishing book store in Melbourne, Australia, Cole’s Book Arcade, and his charming picture books that appeared to have a preternaturally Aquarian Age reliance on rainbows. He has me rather interested in finding one of the Wallypug novels by G.E. Farrow, a series of books influenced by but not nearly as smarmy-sounding as Carroll’s Alice books. He also revisits an author he discussed in issue two. Murray Constantine, who wrote Swastika Night in 1937, was actually a lady named Katherine Burdekin and she wrote a book aimed at children in the 1920s called The Children’s Country under the name Kay Burdekin. In retrospect this is a heavy book for children if they are skillful in picking up on subtext. I wonder how modern, woke audiences would feel about Burdekin’s blurred sex/gender lines.

If nothing else, this issue shows how many books for children and young adults were written by women. Amy le Feuvre is clearly a woman’s name but one could be forgiven for assuming Erroll Collins and EE Redknap were men, writing heavy and at times brutal science fiction with a splash of fantasy for young readers. Nope, those were the writing names for Ellen Redknap, whose hardcore militaristic and intensely martial story lines ensured that a reader like me would not have enjoyed her writing when I was her target audience. What makes this writer all the more remarkable is how… girlie she was. Evidently she was known as “Goody” as in goody-two-shoes. Deeply maternal and helpful, she raised her siblings after their mother died, lived as a spinster while offering all sorts of assistance to aspiring writers, all the while writing books aimed at aggressive pre-teens entitled The Black Dwarf of Mongolia and The Hawk of Aurania.

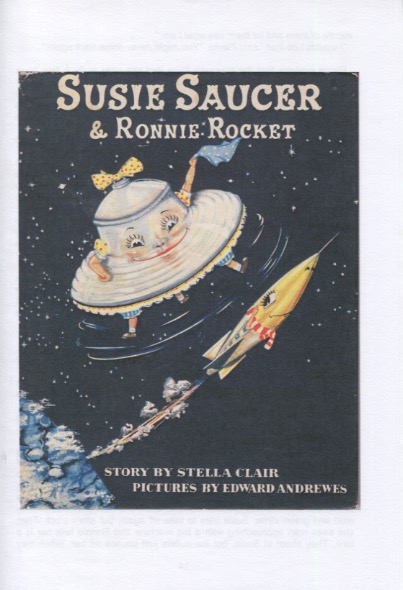

The oddest book Mikul looked at is the utterly bizarre, plot-driven Susie Saucer & Ronnie Rocket by Stella Clair, illustrated by Edward Andrewes. Whew lad, this is one hell of a book and hopefully Mr. OTC adds this to the “need to buy if I come across it” list. Heavily influenced by the 1947 description of “flying saucers” and the horrors of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, this 1957 children’s book is a synthesis of that which is cute, that which is arcane, and that which is absolutely fucking terrifying.

Stay with me: Okay, so on Venus, the business men decide to stop making flying saucers and Susie is one of the last ones constructed. Susie is recruited by “Flame,” who is a Lord of Venus, to be his… I don’t know, spaceship ward, and he places her in service on a huge spaceship carrier called Jupiter. On a mission to Earth, Susie meets a rocket, Ronnie, and the two race each other and get up to all kinds of shenanigans but Susie gets stuck in a pond and she and Ronnie are found and taken in to be examined by Earthlings, certain Ronnie and Susie are enemy weaponry. Ronnie gets help, Susie is rescued but Ronnie is caught again and turned into a bomb and the UFOs have to save the day.

This story is full of absolute WTF-ery that make it absolutely mind-boggling, especially given how adorably illustrated it is. Here Mikul is discussing when Susie and Ronnie meet:

They strike up an awkward conversation, with the rocket’s “gorgeous dorsal fin” making Susie’s magnet quiver.

Later, when Susie is captured, the attempts to disassemble her sound very close to rape. It’s a weird little book to be sure.

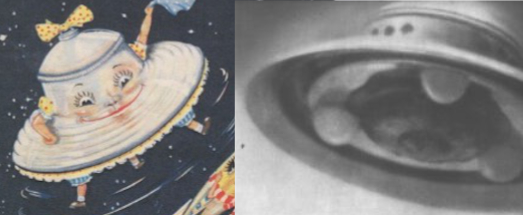

The part I liked the best about Susie is clearly she was a means by which true believers in UFO-ology were trying to make the topic approachable for children, going so far as to mimic a widely known but disputed photograph of a UFO.

The book benefits greatly from its colourful and charming illustrations by Edward Andrewes. Susie, with her ribbons and polka-dot outfits, must surely be the most feminine flying saucer ever conceived. Andrewes based her closely on the iconic flying saucer Adamski claimed to have photographed in December 1952. This looks like a hubcap (probably because Adamski made it from one) and has three round protuberances at its base (probably light bulbs). In Andrewes illustrations, these become Susie’s three legs, clad in polka-dot material with frills.

You know terribly scary and awful Christian cartoons are? Like Davey & Goliath and basically all those weird vegetable and fruit animations? They mean well but they are invariably off-putting at best, nightmare-fuel at worst. It’s good to know ufology attempts to recruit the young suffer from similar shortcomings. I guess dogma marketed to children will be a tough row to hoe, so to speak.

There’s much more to the article than this and I’m holding myself back because this is a “worth the price of admission” article. Actually, every article in this issue is worth the price of admission. If this is the first time you have encountered Chris Mikul’s work on my site, I should apologize for my sloth of late because you really need to be made aware of him annually, if not quarterly. I plan to discuss his most recent book, My Favorite Dictators, here as soon as I reasonably can, and you can have a look through my “Authors A-Z” list and see more of my looks at his work. Also, if you are interested in buying issues of Biblio-Curiosa or Mikul’s equally fascinating Bizarrism, you can contact him at cathob@zip.com.au to get costs and shipping rates.

Mikul’s look at children’s literature was an excellent starting place to discuss media for children that ended up being unintentionally disturbing to children or alarming to adults. And what better time to consider terrifying children than during Oddtober?