This post originally appeared on I Read Odd Books

Book: Sleeping Beauty: Memorial Photography in America

Author: Stanley Burns, M.D.

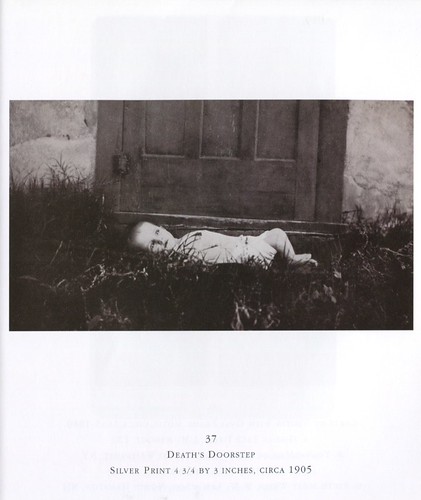

Why Do I Consider This Book Odd: Contains photographs of dead people, many children, from the turn of the 19th century and while beautiful, it is somewhat morbid. If you have an aversion to such photography, give this review a skip.

Type of Book: Photography

Availability: While I am unsure if this book is considered rare, per se, it only had two editions. Mine is from the second edition. Clearly, the first editions are far more expensive, but the second editions are pricey as well. One can obtain a copy of either edition if one is willing to pay between $400-$1000 USD. Had The Strand not had a copy with a damaged book jacket selling for cheap, I would not have a copy. Amazon appears to be the best source for this book but it’s hit or miss.

Comments: This book is one of my most prized books. I waited for almost a decade to be able to afford a copy, and even after I ordered it, I bit my nails until it arrived for fear that there was some mistake and they were going to notify me that I had been undercharged. Reading this book on loan from a library began my intense interest in memorial and death photography. It is one of those treasured books that I still cannot believe I own.

This book examines postmortem photography from 1840-1930. A practice that may seem morbid to some, death photography was actually quite common for those who could afford it. In a time when photography was still expensive, many times these photographs of the dead would be the sole picture people would have to remember their loved one, especially if the deceased was a child. The pictures in this book will often stay with those who have just glanced through it. After discussions online, there have been a number of times wherein people who could remember a particular image sent me messages asking me if I could provide details. One photo in particular, “The Murdered Parsons Family,” generates more messages than any other. The picture shows a father, a wife, and their three children, laid out on a bed like cord wood, bullet wounds visible on their faces and bodies. I think this is the most remembered picture because it plays into so many different modern fears. Home invasions, violent murder, children in danger. Many of the pictures in this book depict deaths that seem like they could no longer happen to affluent Americans. Emaciated babies and typhoid victims are thin on the ground these days. Kids dying from bullets are not. I think every person willing to have a look at this book will find a picture that will haunt them. Or, as was my case, many that will haunt them.

But most of the time we will have no real idea why certain photographs affect us other than the obvious pathos involved in looking at the dead. To this day I am not sure why I am so deeply interested in these photographs. Stanley Burns says in his preface, “Nineteenth-century Americans knew how to respond to these images. Today there is no culturally nominative response to postmortem photographs.” And that is why many of us, myself included, are awe-struck by these photographs, unable really to explain what we find so appealing and appalling about them.

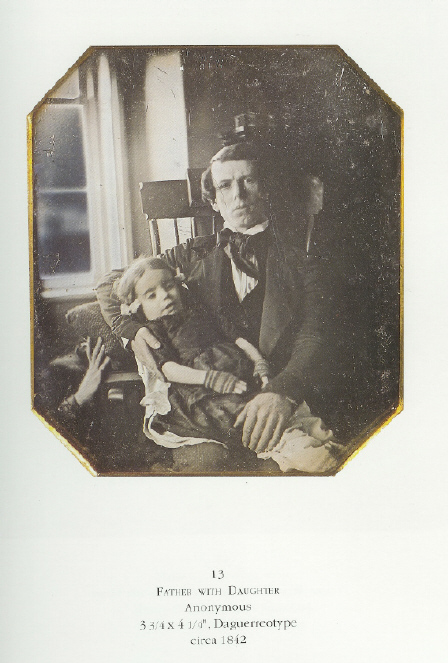

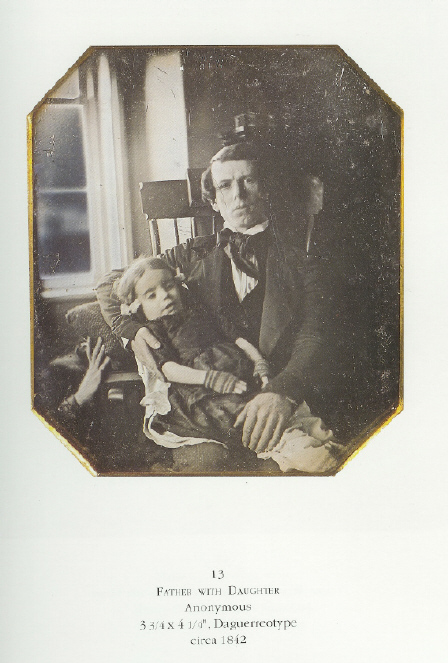

Though many pictures in this book affected me, during the reading I did before writing this entree one photograph seemed to affect me the most. And bear in mind that I can on some level state intellectually what interested me in this photograph, there is likely a visceral response that I could never express.

This picture is quite striking to me. As Burns indicates in the notes for this picture, it is uncommon to see fathers posing with their dead children. More often than not, mothers posed, or the child was photographed alone. That the father is the primary parent in this photograph is touching because it is so atypical.

Another poignant part of the picture is not immediately obvious, but if you look in the lower left hand corner, you will see the mother’s hand stabilizing the pillows that prop up her dead daughter. That action was among one of the last things she could do to help capture the memory of her child, a little girl whose death took her far beyond the reach of a mother’s desire to nurture.

And my god, the little girl… In many of the photographs in Burns’ book, the children look like they are sleeping. But some look obviously dead, with bloody faces, severe emaciation, or evidence of disease on their still bodies. This little girl straddles the line between sleeping and hard death. As you look at her, you can tell there is something very off about her eyes and the pose she is in. It looks like she is either beginning rigor mortis or leaving it. But by not appearing that she is sleeping, and by not looking as horrible as some of the corpses in this book, she is in a netherworld where, to the casual viewer, it may not immediately be evident what is happening.

This and other pictures like it give lie to some of the ideas I have learned from history. Many sources claim that until the time of American urbanization and complete industrialization, life was cheap and the lives of children even cheaper. These sources claim that couples had many children not only to use as a labor force, but also to ensure that at least a couple survived to adulthood. Childhood was an unsentimental time because parents could not get attached to their children. The pictures in Sleeping Beauty make it clear that even when money was tight, when photography resources were limited, and even when life seemed cheap, it was never really quite that way. People deeply mourned their dead, especially their children, and paid money to make sure that there was some evidence that a dead person existed beyond simply the memories of those who loved them. This comforts me. It tells me that human beings are often much the same no matter when they lived in history. These pictures show me that life was not so cheap even when I assumed it was.

The book is filled with pictures like this, heartbreaking looks into the ways that parents handled the deaths of their children, but not all the pictures are of families. Badmen in their coffins, murder victims, as well as photos of memorial picture presentation in jewelry or watches. Hopefully, one day this book will be released for a third printing, making it somewhat more affordable for people to get their hands on a copy. It is truly a beautiful, haunting book.