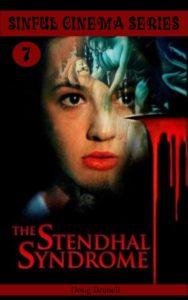

Book: Sinful Cinema Series 7: The Stendhal Syndrome (say this five times in a row as fast as you can)

Author: Doug Brunell

Type of Book: Non-fiction, film criticism

Why Do I Consider This Book Odd: Well, it’s not that odd, strictly speaking, but discussing Doug Brunell’s Sinful Cinema series has become as close to a tradition as I am capable of establishing.

Availability: Published by Chaotic Words in 2024, you can get a copy here.

Availability: Published by Chaotic Words in 2024, you can get a copy here.

Comments: Every year Doug Brunell, using a system unknown to me though I picture him pulling titles of all known horror movies out of a very large hat, randomly selects a film to dissect for his Sinful Cinema series. These film examinations are a hoot, especially when the film he discusses involves a topless investigator busting a human trafficking ring, or a paranormal fraud wrecking lives, or a weird island in Greece where a vampire is entombed, sort of. I think that the “hoot” element for me is that the movies he discusses are generally forgotten or under-known, which generally points in the direction of the films being fringe or loony in some manner, and the real value of the book comes about when Brunell examines the film and finds value that would have gone right over my head without his guidance.

I won’t say he redeems those films, because each one, though sort of awful in execution, has something of great worth in it somewhere and I can count on Brunell’s sharp eye and erudite analysis to show me where that value lies. I also greatly appreciate that Brunell marries his erudition with a willingness to take each movie seriously. I mean honestly, The Abductors was an absolutely horrible film, but after reading Brunell’s open-minded take, there was more to the film than I absorbed in my first watch, probably because I got really distracted by the heroine’s refusal to cover her breasts, even during a frantic car chase. Brunell also goes beyond basic criticism and investigates those involved in the films, sharing all kinds of interesting trivia about the script, crew and actors.

All of these films, given their fringe or forgotten status, were wholly new to me. I watched them before I read Brunell’s take and his books gave the films some gravitas, but because they were unknown to me, I had no preconceived notions regarding them. So it shouldn’t be surprising that I had some trepidation about this year’s film, Dario Argento’s The Stendhal Syndrome.

When I was much younger, I tolerated Dario Argento and the other Italian directors who created the “giallo” style of film making. I found the plots to be too labyrinthine and, frankly, pompous for them ever to really resonate with me. But at the time, such films were very hard to find and watch in Farmer’s Branch, Texas, so anything new beyond what we could rent at Blockbuster or watch on cable was going to be a hit, even if only temporarily. The closest I can come to saying I really like an Argento film is to assert that Suspiria was a pretty good movie (the original, the trailers for the remake seemed so awful that I laughed when I saw one). I wondered how Brunell would handle a film that has been well-discussed in film circles and has such a divisive quality to it, for The Stendhal Syndrome is a movie people either love or hate. I did not like coming into this knowing I really disliked the film he was discussing. I wondered if he would be able to pull off his bad movie redemption act. I mean, if a man can discuss The Abductors in a manner that on some level redeems the hilarious awfulness of it, perhaps he could sway me on The Stendhal Syndrome.

Brunell himself had some of the same trepidation I felt. He wondered if he should even discuss it even though it was the film that he picked during his annual random selection.

Believe it or not, The Stendhal Syndrome was another random pick. It just so happened, however, that it was a film I had seen before. Incidentally, it is also my favorite Dario Argento movie. These things, along with it being well-known and newer, made me reconsider several times if I wanted to write about it. After all, a lot has been written and said about the film, and many of the people involved in it have been interviewed (and I knew my chances of securing interviews with any of the Argento clan was slim-to-none). The biggest question I had was: Could I add anything new to the discussion of this movie?

For me, the answer is yes, Brunell added something new to the discussion because even though Argento is well-known and this film is somewhat controversial, I have not read any criticism of it, and I suspect a lot of those who love or hate the film are in the same boat. So even if some of his observations are not groundbreaking, Brunell’s accessible writing coupled with his unironic affection for the films he discusses, even the hilariously shitty ones, means that people who don’t want to wade through dry and jargon-heavy criticism just to understand what the hell this film was trying to accomplish will find useful and probably new information.

I recall watching this film many years ago when I first moved to the Austin area. Vulcan Video, now gone forever, had a more extensive foreign horror section and I came across a lot of excellent Japanese and Italian horror I never knew existed. I absolutely despised this film and I realize that part of my dislike could be chalked up to not fully getting it. And I guess that is a shame because I didn’t have the visceral dislike of Asia Argento that I currently have. Even had I liked it then, I can’t help but wonder how I would react to the film now given the way Asia Argento’s life has played out in the news over the last few years. Brunell briefly addresses the “problematic” nature of Asia Argento, acknowledging it then promptly moving on to discuss the interesting details I missed.

I can’t say Brunell’s discussion of this movie redeemed it for me, but it did enable me to see past my dislike of Asia Argento long enough to take on what Brunell has to say about the film. I will attempt to give a very brief synopsis of the plot: Anna Manni is a detective investigating a rape case when she collapses at the Uffizi Gallery. She suffers from Stendhal syndrome and becomes agitated or enters a completely altered mental state while in the presence of great works of art. This tendency of hers made it very hard initially to know what the hell was actually happening and it was comforting to learn that even learned critics still don’t agree on what actually happened in the film versus what Anna perceived to be happening. Anna is helped by a man named Alfredo, whom we learn has stolen her gun when she was unconscious and later sexually assaults her. Anna experiences an unraveling, her personality changing radically as she becomes hardened, more masculine in her approach to sexual and romantic relationships. Alfredo continues to stalk her and it seems as if Alfredo has killed Anna’s boyfriend, a man named Maria, but we later learn he could not have been responsible for Maria’s murder. To reveal who did it will ruin the film for those who have not seen it, but hopefully this is enough to frame this discussion.

I can’t say Brunell’s discussion of this movie redeemed it for me, but it did enable me to see past my dislike of Asia Argento long enough to take on what Brunell has to say about the film. I will attempt to give a very brief synopsis of the plot: Anna Manni is a detective investigating a rape case when she collapses at the Uffizi Gallery. She suffers from Stendhal syndrome and becomes agitated or enters a completely altered mental state while in the presence of great works of art. This tendency of hers made it very hard initially to know what the hell was actually happening and it was comforting to learn that even learned critics still don’t agree on what actually happened in the film versus what Anna perceived to be happening. Anna is helped by a man named Alfredo, whom we learn has stolen her gun when she was unconscious and later sexually assaults her. Anna experiences an unraveling, her personality changing radically as she becomes hardened, more masculine in her approach to sexual and romantic relationships. Alfredo continues to stalk her and it seems as if Alfredo has killed Anna’s boyfriend, a man named Maria, but we later learn he could not have been responsible for Maria’s murder. To reveal who did it will ruin the film for those who have not seen it, but hopefully this is enough to frame this discussion.

Brunell does an apt job of discussing the symbolism of the pieces of art that cause Anna to dissociate or descend into hallucinatory psychosis, but the best part for me was his explanation of why it is Anna was so awful to me. I recall not really caring about what happened to Anna because she was so unpleasant. Nasty, even. Her reactions to others were, in my much younger mind, aggressively rude. I didn’t understand her but Brunell goes a long way in correcting some of my assumptions about Anna.

I think most people are familiar with the idea that when women experience extreme stress, we often end up messing with our hair. Anna cuts her hair short after her attack, and even her brother teases her that she looks like a boy, to her consternation. Brunell makes the argument that this common act of cutting her hair was Anna attempting to become more masculine, dealing with the trauma of rape by adjusting her personality until she exhibits masculine traits. She began with her hair, but as she dissembled further she began to engage in self-harm. However, instead of harming herself in a covert way and on a place on her body that was not visible, she was exhibiting a need to appear more masculine. When she deliberately breaks a wine glass in her hand, this is how Brunell dissects the scene:

I think most people are familiar with the idea that when women experience extreme stress, we often end up messing with our hair. Anna cuts her hair short after her attack, and even her brother teases her that she looks like a boy, to her consternation. Brunell makes the argument that this common act of cutting her hair was Anna attempting to become more masculine, dealing with the trauma of rape by adjusting her personality until she exhibits masculine traits. She began with her hair, but as she dissembled further she began to engage in self-harm. However, instead of harming herself in a covert way and on a place on her body that was not visible, she was exhibiting a need to appear more masculine. When she deliberately breaks a wine glass in her hand, this is how Brunell dissects the scene:

Anna breaks the glass in her hand and does not seem to react at all to the pain, internalizing it much as a man would do.

He elaborates more:

Cutting her hand is done in public, where most females who resort to cutting do so in private. It is also seemingly done “accidentally,” where females traditionally do it deliberately and with ritual.

Anna’s last name, Manni, evidently translates to “a fierce or strong man.”

She later engages in a sort of masculinization of her sexuality. She is seeing a man named Marco who clearly adores her but is utterly tone deaf to the very real distress Anna is exhibiting. Anna reveals in therapy that she shrinks from the idea of being fucked and prefers the idea of being the one who fucks. When Marco pushes her to have sex, she responds in an increasingly hostile manner that he does not pick up on. When Anna asks him if he wants to “have sex,” when she generally referred to it as “making love,” she is showing a departure from the more romantic view of sex. It gets creepier:

When she spins him around and pushes him face first into the wall and then begins thrusting at him from behind, it is a decidedly male act.

[…]

When she tells him that she is now fucking him and starts to reach down his pants, Marco demands she stop. She tells him to “shut up,” and that she does not want to hear his voice. As if that were not enough, she tells him she is not finished yet and throws him to the ground and kicks him.

Another wrinkle in the film that Brunell helped smooth for me was the reason why Alfredo, who raped and killed a number of women, didn’t kill Anna and kept stalking her. This was an especially sharp observation on Brunell’s part. You see, after she collapses the first time in the film, she loses her identity. It takes her a while to regain her sense of self, her psychic slate wiped clean. Alfredo sees the state Anna is in after she is overcome by art, and it affects how he treats her when compared to his usual victims:

Another wrinkle in the film that Brunell helped smooth for me was the reason why Alfredo, who raped and killed a number of women, didn’t kill Anna and kept stalking her. This was an especially sharp observation on Brunell’s part. You see, after she collapses the first time in the film, she loses her identity. It takes her a while to regain her sense of self, her psychic slate wiped clean. Alfredo sees the state Anna is in after she is overcome by art, and it affects how he treats her when compared to his usual victims:

It seems clearer in hindsight than it does during the scene, but Alfredo is toying with Anna and wants her alive so that he can experience her purity repeatedly. If he can have her as she was in the museum, forgetting all sense of self, it is like having a fresh victim every time in the same person.

My first and sole viewing of this film was definitely hampered because I did not understand why Alfredo became so obsessed with Anna. She was pretty, sure, but nothing about her seemed to spark such dedicated obsession. I get it now. And I can also say that much of this movie is indeed better understood in hindsight. It is a film you will probably need to watch several times to really see all that Dario Argento wanted his audience to know.

Brunell explains further:

Anna’s mental collapse began after experiencing the Stendhal syndrome and exciting something in Alfredo, who treats her differently than he does his other victims. Art has acted as the catalyst, and now, as she actively pursues art on her own, her downfall will be hastened.

Brunell does a fine job of making clear the color symbolism, art meaning and psychological motivations in The Stendhal Syndrome but in the end I still don’t like this film. I understand it better, but even after Brunell’s careful examination I still find myself confused as I marry together his measured evaluation with my own memories of the film. Was Alfredo somehow possessing his victim even though he was alive when she begins to adopt masculine traits? I have no idea.

But it’s still sort of worse than that because I also wonder who on earth bought Asia Argento as a police detective, be it now or then. Her status as an art-loving law enforcer was on par with Tara Reid as an archaeologist in the stinker Alone in the Dark, or Denise Richards as a nuclear scientist in the Bond film, The World Is Not Enough. And let’s not get into the whole “watching his daughter get raped in one of the most sadistic scenes ever is gross” accusation levied at Dario Argento. That one doesn’t actually carry much weight with me because it gets leveled at every parent who directs their child in a film that isn’t G-rated, but it is something that gives this film just an extra layer of “ick” when one considers the role Asia Argento played in the rise of and eventual marginalization of the “me, too” movement.

Overall, I think Doug Brunell made the right choice to discuss a famous film that he had already seen. I can understand why he was concerned that his take on the film would not be fresh and I think following the rules he set out for himself just makes sense. This was one of his strongest Sinful Cinema examinations and it enabled someone who outright dislikes the film and the female lead to see a lot more worth and nuance in a performance that seemed disjointed and bitchy when I first watched it (for what it’s worth, my dislike of Asia Argento began long before accusations against her as an abuser and worse came out – her role in The Heart is Deceitful Above All Things rubbed me the wrong way, so much so that I began to refuse to watch anything else she was in). I really appreciated the art discussions because when I saw it all those years ago the Internet made assembling information like that a lot harder and I had little incentive to revisit the film.

The book suffers a bit because it didn’t bring any of those “wait, that was the woman from Last House on the Left” moments, and of course he was unable to speak to either Argento. Still, he has a long and interesting discussion with Troy Howarth, a horror movie fan and critic, and that interview is one of the “worth the price of admission”chapters in this book. I was afraid I would leave this book without any of the more joyful revelations I had with some of his earlier books in this series, but the inclusion of Howarth exposed me to a writer I had not heard of. He has a book examining the film, Alice, Sweet Alice, that I almost discussed this Oddtober but rejected in favor of Bad Ronald.

So even though I didn’t like this year’s Sinful Cinema movie offering as much as previous years, it wasn’t Brunell’s fault that I am just not that into giallo/rape revenge films or the Argentos in general. In fact, he gave me different perspectives to think about regarding the film and now I have a new author to read. All in all, if the movie was a miss, the book definitely is not. Argento completists may want this on general principle but if you are less familiar with Dario Argento, this would be a great primer to consult as you get your feet wet. This book may not be for everyone but I highly recommend it for those who both love Brunell’s sharp but open-minded criticism and this genre of film.