Book: Beyond the Dark Veil: Post Mortem & Mourning Photograph

Author: Jack Mord

Type of Book: Non-fiction, photography, death photography, mourning photography

Why Do I Consider This Book Odd: Photos of dead people, etc.

Availability: This was beyond a doubt the most involved copyright page I’ve ever seen in a book. Shortest publisher name behind this book was Last Gasp, this book was published in 2014, and you can get a copy here:

Comments: All the death photography books I own are in some regard beautiful. The Burns Archive books are all substantial yet minimalist in their arrangement. Beyond the Dark Veil is more ornate, a gorgeous little book, with gold-edged pages and a gold embossed cover. The pages are thick and glossy and I felt like I needed to don gloves before flipping through it. I’m lucky enough to own some amazingly beautiful books and Beyond the Dark Veil takes a certain pride of place among them.

I am harping on this book’s beauty because this book really is a visual and tactile experience. All photography books are visual, of course, but among people who accumulate books we occasionally come across a book that is just above and beyond, constructed in a way that makes you want to hold it and stroke it and just gaze at it lovingly. This book has interesting information about death photography and funerary customs, and deviates a bit by offering photos of the sick and dying, as well as customs of burial, but I’ve quoted from books about death photography and cemeteries in several entries on this site. So I don’t plan to quote too much information from this book.

Instead, I will quote from the introduction, entitled “Remembering Death.” Written by Marion Peck, herself an artist who creates gorgeous, visually compelling paintings, this introduction captures the loveliness of the book. I think the final paragraph in her introduction very well sums up the photographs in this collection that speak to me the most:

In a sense, these photographs are like ghosts. They are the shadows of people who once lived actively and breathed in a present moment, who saw the blue sky above their heads and might have felt the same passions, joys, and sorrows in their hearts that we feel in our own. If we can quiet ourselves enough to spend some time with these ghosts, contemplating, listening to them, we may learn from their great wisdom. It is the wisdom of ancestors, of those who came before. What we are, so once were they. What they are, so we shall be.

I don’t know if I can ever really explain why I have such a love of cemeteries, death photography, funerary statuary, and most of the ornate customs and accessories of Victorian death. But on some level I think I am learning from the dead. I am godless. I fully expect that when I die I will cease to exist – no heaven, no reincarnation, no posthumous salvation. But we don’t know, really, what happens when we die. Modern medicine seems to think that the brain protects us from the worst horrors of death, that the parts of the brain that experience great pain and fear shut down and we experience only the brightly-lit sensations of awe and wonder as we leave. I think I wander cemeteries because I want to know what awaits me and am studying all the options.

Part of it too is that I am one of two leaves left on a withered branch on a spread-out family tree. There won’t be mourning children and grandchildren or bereft siblings when I go. If I die before Mr OTC, I won’t have a headstone. I won’t be photographed. I will be cremated and hopefully poured into some paint or concrete and something interesting made of my ashes. All the evidence of death I sift through will not be mine so I have to observe now because I will never be among those who are buried and presumably know. And that’s good. I don’t really care if I have these customs applied to my death.

But at the end I wonder how much anyone can really control the customs that others use to navigate the death of loved ones. My mother, by her own request, has no stone and her ashes were scattered on private property that we need special permission to access. Not having that place I can go to visit, to speak to her, is a lot more troubling than I expected. These customs we have built up over centuries of civilization may be steeped in religion that means nothing to me but the customs came about as we human beings struggled to cope with death, to ease the blow, to be able to remain tethered to the dead because even the most hardened unbeliever feels forsaken when she realizes she will never again be in the presence of her mother. In the absence of a place to visit her, I have created a sort of shrine to her. I didn’t think about it too much as I did it because my actions were really mindless reactions, but I have some of her ashes, a couple of her prized perfume bottles, small gifts she gave me, some of her parents’ belongings, all behind a glass-fronted shelf in one of my bookcases. It almost seems like it is an instinct to demand a permanent place to mourn the dead and if the dead prefer not to have a static mourning place dedicated to them, those who miss them will do what is needed to be able to commune with them.

We do these things because it is part of being human. These photos show me that.

But even as I feel a bit melodramatic writing this out, the fact is that we do what we do for the dead so that we can remember them and so that we can be remembered because it is daunting to think that there will be a time when no one alive knows us. These traditions are an attempt at permanence, and given my own recent experiences, it’s an attempt I understand all the better.

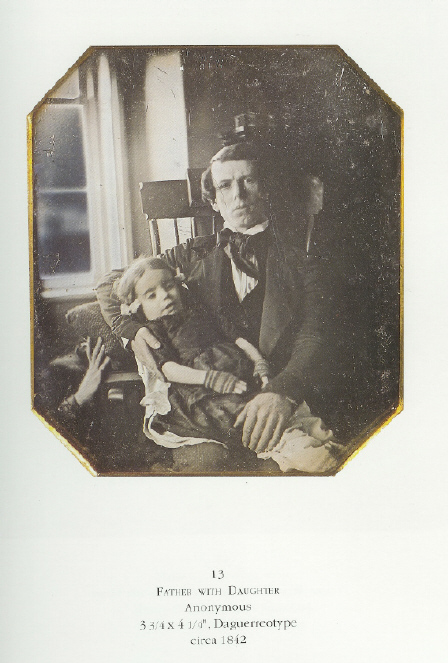

Under the cut are the photographs that resonated the most with me, presented with only enough comment to give them context.