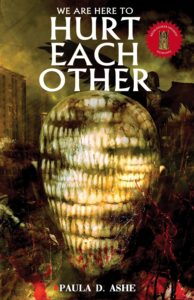

Book: We Are Here to Hurt Each Other

Author: Paula Ashe

Type of Book: Short story collection, horror, extreme horror

Why Do I Consider This Book Odd: It’s hard to take me by literary surprise. I absolutely was not expecting what this book delivered.

Availability: Published in 2022 by Nictitating Books, you can get copies here. For the record, I read the Kindle version.

Availability: Published in 2022 by Nictitating Books, you can get copies here. For the record, I read the Kindle version.

Comments: This book is perfect to start off with for Oddtober 2024. I’ve been on a horror kick lately, and luckily most types of extreme horror lend themselves well to oddness. This book is not in-your-face weird, but rather is weird in that creepy, unsettling way that is often hard to explain. Paula Ashe is a rare writer in her willingness to explore the minds of both the victim and the assailant without sentimentality or a pious morality. Rather, she looks at the human condition with a sharp, focused eye, showing us the will of the victim and the will of the abuser, sometimes blurring the lines between the two without pandering.

Ashe had to defend this approach in her own epilogue. She explains that people actually do take value in the way she presents abuse, saying, “…there are other people who read my work for solace. For understanding. For a bizarre and bitter reprieve.” I am one of those people. As long-time readers of this site may recall, the gut punch from fiction like this was better for me in the end than years of therapy wherein all I was permitted to do was navigate my own suffering rather than build a foundation of knowledge about the human condition. It’s heartbreaking to realize we live in a culture wherein a woman who has written some of the best horror fiction to come across my radar has to apologize for daring to explore the depths and motives behind human evil. Wonderful…

This is a relatively short collection – eleven stories in 133 pages – and you can easily read it in one sitting. I’ve reread the whole of it a couple of times now, and have read two of the stories several times as I attempted to run to ground some of the names and spells mentioned in them. Ashe merges the ancient into the modern and mixes her own horrors with established devils with such skill that I still am unsure if some of her stories are wholly of her own creation or if my research skills have failed me. She inspired me to dig deeper, and even if her prose had fallen short, spurring curiosity beyond the book itself is often worth the price of admission. Luckily, her prose was on the mark, visceral and beautiful. Absolutely savage in some places. She keeps a steady balance between the gloriously cruel and the bitterly hopeful.

One of the many charms of this collection is that Ashe experiments in style and method of story-telling. The story “Grave Miracles” will remind younger readers of “ritual” creepy pastas, wherein an authoritative, omniscient voice gives instructions so the reader can perform a specific series of steps to succeed in paranormal games or endeavors. Ashe constructs her story “Grave Miracles” using such a framework, outlining the startling steps one would take to bring a dead wife back to life and the things that will have to happen to keep her “alive” and flourishing. This story is immediately followed by “Exile in Extremis,” an email exchange between an investigative reporter and her contacts at a magazine. The magazine has published her story about grave robbing, young women coming back from the dead, and an entity known as the Priest of Breathing, and the editor and the magazine CEO need her to reveal her sources. A police investigation was launched as a result of the story and the journalist, Elle, sharp and nearly-unshakeable, does all she can to protect the editor from probing into the story any further. The story manages to be horrifying yet amusing, as Elle deftly uses illegal tactics and the threat of social embarrassment to protect innocent but annoying people from themselves.

Another surprise for me was Jacqueline Laughs Last in the Gaslight. I’m no “Ripperologist,” in that I can’t recite every little bit about the Jack the Ripper killings, but I’ve swam in that true crime lake, reading a lot of non-fiction as well as fictionalized accounts of the Whitechapel murders. I’ve come across a lot of “Jill the Ripper” theories, asserting that Jack was really a woman. This is the best Jill the Ripper story I’ve come across, assigning the protagonist a believable motive and bestowing her with the skills to commit believable violence. I can’t discuss it in any depth without potentially ruining the story, but Ashe both adapts her style to fit what one imagines an omniscient narrator’s voice would sound like as she narrates in 1888, while simultaneously holding on to the earthy, erotic tone the story demands. It’s a delicate balance, and one that Ashe manages marvelously. Describing Jacqueline and her minister husband, she says:

In Whitechapel’s rookery of wastrel the fine pair is as prominent as a hanged man’s prick.

I dare you to write a line more provocative and perfect than this. You can’t do it. You’ll cramp up. If you do try, be sure to stretch out first.

Ashe’s focus ranges from folklore to true crime, ancient history to inter-dimensional time travel. She tackles the horror of what happens when filial evil destroys maternal love and how one woman’s reaction to terrible abuse destroyed the sister she wanted to save. She picks out little, terrible details that, to the right reader, marry together reality and her fiction. A single line from “Carry On, Carrion,” brought to mind one of the more unique details from the miserable story of Tristan Bruebach.* Each story has little details like that, little pieces of horror from real life that make her stories all the creepier because, as we know, the truth is always far more fucked up than fiction.

The final story in the collection, “Telesignatures from a Future Corpse” is likely the piece that is the “price of admission” story for many, and indeed it is a great story. However, I want to discuss the two stories that caused me to spend hours researching old cults and folklore recitations of protection. In discussing these two stories I will likely spoil them some so read on with this in mind.

“A Needleshine Litany” takes place in Ohio in 1924. A old man with loose skin has abducted a little girl, luring her with candy, and intends to do her grave harm. The little girl knows she is in trouble, and right before the man can rape her, she speaks into existence a greater monster that saves her. I was certain the spells the girl uttered had to be part of some sort of folklore belief, and even looked into it but if it is based on something genuinely from spiritual histories, I cannot run it to ground.

I want to go into so much depth in this very short story – only four pages long – but it’s so short that if I do there will be no point in you reading it. However, Ashe so ably and carefully lets us know the races of the people involved, the daily struggles the little girl faced in pre-Depression Ohio, the way she was treated by others all while the story is set in a closed room with two humans and one force of evil so great that even as the girl summoned it she also cringed and looked away when it arrived.

“All the Hellish Cruelties of Heaven” is a helluva story and the source for the title of this collection. It’s told in first person by Annia of Naples, who by way of the Valley of Ben Hinnom, became a member of the Daughters of the Despairing God, a cult headed by a woman named Judith. The cult is a frightening cadre of immortal (or unmortal, maybe) women who are devoted to Moloch, violence, and suffering. Bare bones story synopsis: Annia tells the reader about her life recruiting for the cult, as well as trying to track down a man she knows is committing horrifying murders, a man who may be as primal a source of misery and chaos as she once was. She is attracted to and tantalized by this unknown man, and I thought I saw where this story was going when she finally finds what she is looking for, but I was very wrong.

Okay, maybe five minutes in I was Googling because Ashe uses real women and mythological goddesses in this story. The women in the Daughters of the Despairing God are fairly easy to identify. Judith, the leader of the cult, is Judith of biblical fame, who used her wiles to seduce Assyrian general Holofernes before he sacked and destroyed her city. Judith in the bible and most of her Renaissance representations in paintings are all careful to gloss over the sexual elements of Judith’s successful ambush, but Ashe understands that sanitizing a woman who drugged and fucked a powerful man so she could cut off his head diminishes the real courage and social pathology at play in Judith’s violent act. She was protecting her people, to be sure, but that could have been achieved by a single knife into Holofernes’s heart. She chose to decapitate him and put his head in a basket, her choice of violence showing that much like the Jacobins, good intentions and extreme violence are too often walking hand in hand.

Another character called Deva is most certainly related to the Hindu goddess Devi, who symbolizes wisdom and beauty as well as blood sacrificial offerings and war. A new convert is named Joanna, after Juana of Castile, who was also called Joanna the Mad. She wasn’t really insane. We see this happen all the time with powerful women of yore (and now, frankly). Juana’s husband and father had a lot to gain from sowing the belief that Juana was insane, similar to how the king of Hungary no longer had to repay a massive debt to Elizabeth Bathory if people believed she and her servants killed hundreds and possibly thousands of peasant girls so she could use their blood to keep her youthful beauty.

But then we have Annia of Naples. She is the narrator of this story and knowing about her historical counterpart is important because Ashe takes the woman whose excesses single-handedly ended the tradition of Bacchanalia festivals in Rome, and places her also in the Valley of Bin Hinnom, walking on the ashes of sacrificed children. In Ashe’s fiction, she may also have served in a Dionysian cult between her stint dancing on the bodies of babies and destroying Roman culture. Like Judith, Annia (who is easier to research under her full name, Paculla Annia) is an amoral force of erotic destruction. She speaks of welcoming the ghosts of victims of a serial killer into her “virgin bed,” a reference to Annia’s former status as a priestess of Bacchus. Such a priestess should have been a virgin, and the female cult she led should have celebrated for three days each year. Before she was shut down and her cult outlawed by Roman law, Annia turned those chaste festivals into days-long orgies, including men, five times a month, with her sons assisting her. Like Juana the Mad and Elizabeth Bathory, Annia’s story may have been exaggerated by a man with an agenda. We know the most about her from Roman historian, Livy, and she may have been a convenient scapegoat for an empire already on the skids.

Regardless, she was cast as a villain and Annia accepts that role without any moral consideration. She is who she is and sees no problem with evil or destruction because it is a part of a larger world wherein the lines between right and wrong, misery and ecstasy are blurred. Annia experiences the senses a bit differently than others and she seldom says what I expect her to say. Upon finding a serial killer known as The Rotting Man, the killer whose victims’ souls Annia lures into her bed, she says:

He is a grammar of putrid colors.

She injects the man with strong opiates and begins to control him.

Over the last few months, he became my drooling idiot, eager to entertain all the strange suggestions my creative consciousness could conceive.

But one day he is able to fight back and injures her and she is immediately swept back in her mind to her days in Gehenna, dancing on the bones of the dead and the man escapes. Deva thinks she should tell Judith what happened but Annia is unwilling to do so because she knows Judith will steal the Rotting Man from her, like he’s a handsome frat boy all the sorority sisters squabble over. She predicts what will happen if Judith comes across her prey:

We’ll find him the next day like we find them every few months; eyes bulging from his head, peering helplessly over the rim of a basket.

It’s like she never left that goddamn tent.

Frankly, Annia seems the better leader among the cult members, as she has the capacity to control her rapacity or channel it in a manner more appropriate to reaching specific goals. But one also gets the feeling that Annia has far better things to do with her time than lead unstable women cursed to reenact their historical acts of evil over and over. She wants to find the source of a frisson of ancient evil she picks up on and wanders the city trying to find him. She has no moral quandaries because Annia understands something dark about the world that is eternal and unbreakable.

Recognizing the universe as it is – a cosmic slaughterhouse unending – is difficult as the machinations of reality function only to deceive sentient beings into believing there is some meaning behind the echoing chaos.

Annia traipses around, trying to appear as bait, skulked about in places where terrible things happen, but one night she finally finds him, the ancient evil that is perhaps as old as she is. I will not spoil the story by discussing what exactly happens when she finds the man, but she does find him, and upon recognizing him, she thinks:

Had it not been for the centuries of sleeping in catacombs, sepulchers, and mausoleum vaults to escape vengeful mobs of priests and politicians, I would have incinerated every single person in that filthy bar…

She later muses on the ouroboros of pain and misery that is and always will be part of the human condition.

Pain is the source of all matter. It is the force that holds the universe together, that will tear it apart, only to rebuild again. Throughout the ages, humanity asks over and over again “why are we here?” and then pretends as if the Void does not bellow the answer back every single time.

We are here to hurt each other. Again, and again, and again, in perpetuity.

I am not a Christian but I recall the lessons of my childhood when I was taught the notion that God permits abject suffering in order for people to be able to show mercy, preferably in His name. Even as a little girl that seemed unspeakably awful. Someone must have agony and misery visited upon them so some random asshole gets to show off their merciful piety? No thanks. But what if it is the other way around? What if those willing to endure The Other suffering in order to be merciful, create the very misery they use to fuel their desire to be do-gooders? There is a tyranny in mercy that is sickening when you realize what the most merciful actually do. Mother Teresa was an absolute monster, praising the miserable deaths of the sick and starving. This was her philosophy stated in her own words:

There is something beautiful in seeing the poor accept their lot, to suffer it like Christ’s Passion. The world gains much from their suffering.

The merciful needing evil in order to be merciful is far worse than the sick and miserable needing mercy for salvation. One thinks that even in a utopia the merciful will poke and prod until a worsened world permits them to assume again their self-appointed role as a giver of mercy. In such a world, if wickedness exists to prop up the good, who is genuinely evil and who is genuinely good? The idea that personal visions of mercy harm the weak comes up vividly in “Bereft” where a woman’s attempts at mercy destroy her sister and show her that she is, in fact, a monster in the mind of the person she hoped to save. There is very little mercy in this book, now that I think of it. A mother is forced to a violent reckoning with her wicked son. To ward off rape a little girl summons a force of far worse evil to save her. A female stand-in for Jack the Ripper ministers to the poor but shows them absolutely no mercy when it comes to her own goals. Siblings who find out their mentally ill, terribly abused sister has given birth, and guilt, not mercy or genuine kindness, guides their reaction.

Ashe writes with a brutal honesty that leaves no room for sentimental happy endings. Evil can only be destroyed by an equal or greater evil, meaning that humanity is and always will be stuck in a cycle of hurting each other for redemption.

This was an astonishing collection. I searched for more from Ashe a few months ago, expecting there to be at least another short story collection or a novel, but couldn’t find one. Today I saw that she has a short story one can read on Kindle but it sounds like it may be an early version of a story in this collection. I hope to read more from her in the future and I hope her philosophies and careful, beautiful, cruel prose find a large audience. I definitely recommend this book.

*Tristan’s killer neatly laid his shoes on his chest. I’ve never read of that happening in any other murder case and it was interesting to see a variation of it in Ashe’s writing. You’ll need to buy Ashe’s book to see where this detail plays out.