I was born in Dallas and have lived in Texas all my life. When I was a little girl, I can remember seeing “colored” entrances, restrooms and drinking fountains in older downtown buildings. Jim Crow was dead, in legalities at least, so no black person was forced into using these lesser amenities, but they had not been removed yet. In some places in older parts of Dallas, such reminders of the nastier parts of racial history in the USA weren’t remodeled or removed until the 1980s.

I tell you all of this because while I was and still am aware that race relations in the USA are difficult, it was still… shocking when I began cemetery investigation and saw that segregation was enforced even in death. The slave and “colored” sections of “white” cemeteries were seldom maintained well, which is not particularly surprising. But I discovered that large chunks of history were lost in those slave and black sections of cemeteries, making even some of the simplest genealogy or historical research maddening, if not completely impossible.

And there’s no way around this expression of sentimentality – often slave and Jim Crow cemeteries are sad places indeed.

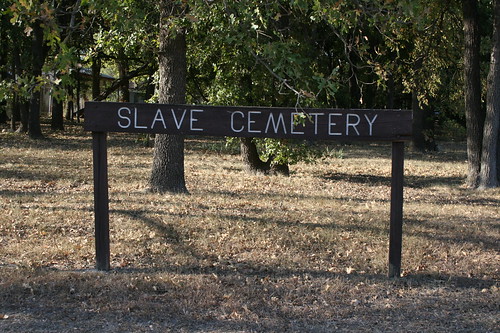

The first slave cemetery I found was in Round Rock Cemetery in Round Rock, Texas. I was there looking for the graves for some Old West villains and lawmen, and was startled when I saw it.

Note that you can’t actually see any headstones beyond that sign.

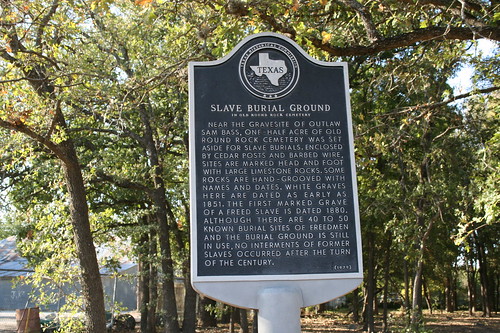

Here’s the historical marker for the Round Rock slave cemetery. It’s worth stating that it appears that mostly freedmen were buried in this section. I don’t know enough about the history of the social differences between being a freedman and a man who had genuinely never been held in bondage. Did people who had never been slaves get buried elsewhere, in a “colored” cemetery? Round Rock cemetery had no “colored” section, so it makes me wonder if all black people were buried in the slave cemetery.

Very few stones are extant in Round Rock’s slave cemetery. If there is a list of plots for this slave cemetery, I was unable to find one (but it’s also been a while since I looked). What stones remain are broken, have fallen over, or are propped up against trees. One very much gets the feeling that groundskeepers may have removed stones to make mowing a bit easier, but that’s just my own jaded opinion.

It was interesting how the slave portion of the Round Rock Cemetery was actually the most peaceful area. It had lots of tree-cover, providing shade. More grass was growing than in other parts. All in all, even with the neglect it was still the most pleasant section of the cemetery.

Because it was clear that stones had been moved and, in some cases, stacked together, I became worried that I was stepping on someone’s burial plot with no way of knowing it.

This stone was quite sad. Those hands at the top of this stone indicate marriage. The hand on the left belongs to a woman and the hand on the right belongs to a man. You can tell by looking at the cuffs. So this was a stone belonging to one half of a married couple who hoped to be reunited with his or her spouse in the afterlife. We don’t know his or her name, and I cannot tell if the stone sunk or was reburied after breaking – I still have an aversion to touching people’s headstones that I cannot explain – but we know this person was evidently happily married. We also know this person either had the funds or had relatives with the funds to purchase a professionally-made stone.

Jesse Wilson led a very long life for a man who most assuredly lived as a slave for the bulk of his time on earth. I think his birthdate is the oldest I have found in a Texas cemetery. Born in 1788, he died in 1870. His stone also gives the appearance of having been professionally-made, or at the very least made by someone with experience in imprinting or carving letters into stone.

The rest of the slave cemetery was far harder to decipher.

Broken stone…

Eroded and broken hand-carved stone…

A pile of broken and eroded stones.

And that was pretty much the whole of the slave section at Round Rock Cemetery. I’d like to go back one day and see what it looks like now, and to do more in depth research and see if there is a record anywhere of all the people who were buried there. It’s frustrating to see a piece of history, especially a history of people whose lives and stories were not respected, more or less obliterated.

The second cemetery I am going to discuss is the “colored” cemetery at Oakwood in Austin. Oakwood was established in 1839, and is large. I’ve only documented parts of it that I investigated as I searched for the graves of the victims of the Servant Girl Annihilator, and the cemetery is huge and sprawling. Oakwood is notable for the graves of a couple of “bad men” but it also has a Jewish section.

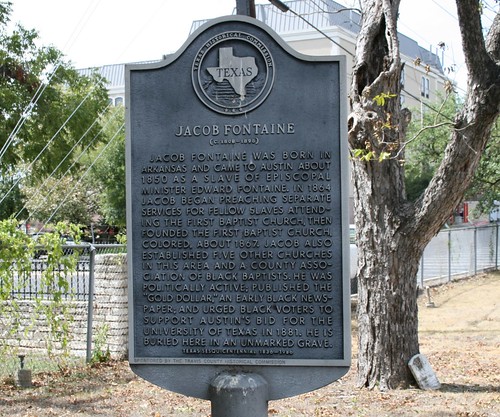

Oakwood’s “colored” section is a small wasteland. I found online plot numbers for this section of the cemetery and around 70% of those plots are visually empty, meaning they have no headstone or grave marker of any kind. I guess that shouldn’t be a surprise when the grave of the man like Jacob Fontaine, a man important enough to merit an historical marker, was buried in the “colored” section in an unmarked grave.

The “colored” section also features a familiar site – broken stones leaning against trees. But Charlie Whitefort’s stone is still interesting. The pointing hand at the top of the stone is a symbol that indicates that the dead person ascended directly to heaven. I also like that Charlie “fell asleep.” He was a toddler when he died. I find it very interesting that this stone does not have the typical iconography associated with dead Christian children – lambs or doves – but rather is clear that this child immediately flew to Heaven when he died.

There were some intact stones in the cemetery, but there were also unsettling sites like this one wherein it is clear there is a family plot but no stones to indicate who is there. The records of who is buried where were not clear to me, relatively shambolic, actually, so aside from family members who may still reside in this area, I don’t know if anyone knows who is buried in these areas where graves are demarcated by borders.

Oakwood’s confusing and inattentive handling of their black residents made one of my investigations impossible. As I learned about the Servant Girl Annihilator murders that occurred back in 1884-1885, I learned most of the victims had been black and most of them were buried in the “colored” section of Oakwood. The frustrating search for the SGA victims will be my next entry, wherein I will discuss the murders and how relics of the reaction to those murders loomed over me for years, though I had no idea the history of those relics.

I know that to people above the Mason-Dixon line and Europe, the slave and “colored” cemeteries are grotesque. It’s hard not to agree with such an assessment. At the same time, had these cemeteries been handled or organized with the smallest levels of care, they could have been excellent sources of historical data. Names could have been gathered from stones, family histories re-established, and people would not have been lost to history. My Servant Girl Annihilator search showed how people of historical interest were lost but I can imagine families all over the world looking for relations who ended up in slavery or whose families descended from slaves and hitting brick walls because cemetery and death records are the lifeblood of genealogy research.

The world is a cruel and callous place, even now. We like nothing so much as to remove from history those we have conquered, those we have wronged.

I am originally from England, I was absolutely appalled when I saw that our local cemetery (Texas) has a ‘black section’. They lied (omitted the truth) about the circumstances of the ‘First Negro…’ who was buried there in 1965. He had a wife, but she died in 1957, so she wasn’t buried at that cemetery.

The south is a really racist place, and even in death, black people are buried in a different section of the cemetery. Segregation hasn’t died, it’s just a lot more covert these days…

Oh yeah… someone wrote an article about the ‘Old Days’- they said that he and his wife were ‘in charge of the kitchen’, at the local hospital. This is when segregation was in full swing! Actually, they were both initially domestic servants, of a rich, freemasonic family. I’ve done some research on my locality, thank goodness for the LDS archives, although ancestry.com owns it all now.

The ‘black section’ is on the less desirable side of the cemetery, on the opposite side of the ‘best side’, right at the bottom of the cemetery. Baptist Christians are amongst the most hateful, racist people imaginable. They’re not all bad, of course not, but they have a large section of racist bigots amongst their ranks.