Murder ballads. What better time than Oddtober to consider music created to memorialize (or aggrandize) terrible murderers, unfortunate victims or horrible crimes in general. Though these days murder ballads cross into multiple music genres, they are still a popular story-telling vehicle and far more common in contemporary music than I expected when I began looking into them. Specifically, I stumbled across a Norah Jones video for a song called “Miriam” and it caused me to start looking into similarly unexpected songs from fairly anodyne singers and before you knew it, I was down the murder ballad rabbit hole.

Like so many art forms that deal with murder and death, murder ballads are probably Germanic in origin, though such songs were contemporaneous in Scandinavia and the British Isles. Evidently some musicologists and historians disagree, mostly Americans, because when you research murder ballads, you inevitably find arguments between those who feel that murder ballads are a very Appalachian thing and those who feel that murder ballads were a staple of black culture and that whites yet again have taken credit for something they didn’t do. It’s not a theory without merit, as arguments about the origins of jazz and the blues continue to this day even though gadflies have a very hard time justifying their point of view. But it has to be said that neither the Appalachians nor the black communities in North America created murder ballads, though they certainly put their own spin on the traditional songs.

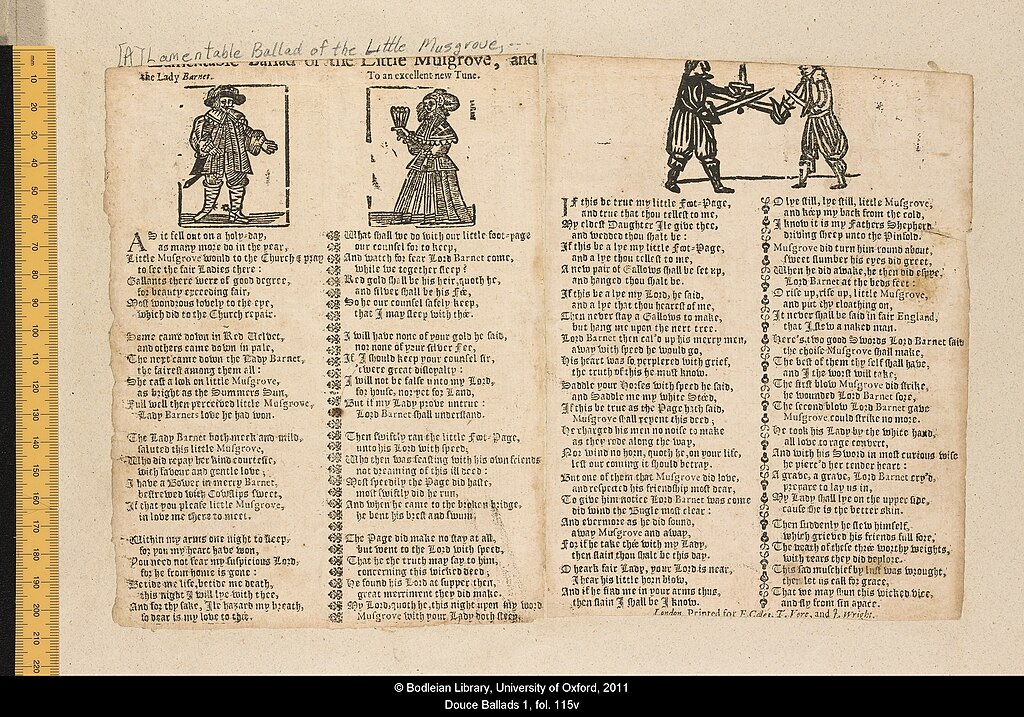

The first known (or at least the first known recorded) murder ballads are “Little Musgrave and Lady Barnard” or “Matty Groves” from the late seventeenth century, and the “Berkshire Tragedy” from early eighteenth century. The former is a corker of a song, likely from England, telling the story of a young wastrel who goes to church merely to gawk at the pretty ladies and manages to catch the eye of one Lady Barnard, who fancies him and decides to have an affair. When Lord Barnard finds them in bed, he challenges the naked Matty to a duel, killing him but not after being wounded himself. When he returns to his good Lady she tells him she’d rather have the dead commoner as her lover than him and Lord Barnard kills her too. He eventually feels deep remorse for what he did and buries the lovers in the same grave, placing Lady Barnard’s body atop that of Matty, which is more fitting given her noble birth and I think we can all agree makes perfect sense.

“The Berkshire Tragedy,” which some far more learned than I am think is a variation on an earlier song called “The Bloody Miller,” relates the story of a miller who comes across a pretty girl and tells her he will marry her if she sleeps with him. Believing him, the girl sleeps with the miller only to find out he had no intention of marrying her when he begins beating her with a stick. She begs for her life but he cuts her throat from ear to ear (as the story-teller in “Miriam” did to her unfaithful beau, punishing him “from ear to ear”). He dumps her body in the river and when he returns home covered in her blood, he is captured and sentenced to death.

Before he is hanged he hopes his story will prevent any other gross young men from committing rape and then killing their victims, because presumably in the late 1600s, men committing rape by fraud and then murdering the tragic woman was a common enough problem that this song served as a public service announcement of sorts. “This is your brain on drugs, also don’t rape and murder women you promised to marry.”

Murder ballads generally have one of only a few story lines:

–A man defiles a woman in some manner, be it rape or murder or both, and meets a brutal end himself.

–A doomed couple pair up in defiance of marriage or other social constraint, like parental disapproval or class markers, and one or both meet a brutal end at the hands of a jealous spouse or outraged community.

–A paean to rakish or exciting criminals like Robin Hood or stylish highwaymen who often meet a terrible end but are remembered fondly by the common man.

The traditional categories are seen over and over again, with a lot of crossover, and for this first part, I’m going to talk about the “kill loose women” and “doomed lovers” categories. The themes from “The Berkshire Tragedy” and “The Bloody Miller” show up in American murder ballads from the nineteenth century to current day. “The Knoxville Girl” was first released on record in 1925, and was already well-known by then. The song borrows heavily from its source. A man named Willard is courting an unnamed American girl from Tennessee and pressures her to sleep with him. She does, and, eventually, one evening on a romantic walk, Willard brandishes a stick and begins to beat her to death as she pleads for her life.

A version of this song was recorded by The Louvin Brothers in the 1950s in a bluegrass style, and in their version, Willard evidently justifies his actions because he believed she had a “dark and roving eye” that made it impossible for him to marry her.

In short, she slept with him before marriage so she was probably a slut and you can’t turn a ho into a housewife so best to beat her to death and toss her in the river. Don’t worry, though, Willard does go to jail for life. His unnamed victim is almost meaningless in this song, with the focus being on Willard’s desire to be rid of a woman who lacks virtue, and it depends on the listener’s reaction as to whether or not she is being truly villainized in this song, but her lack of a name and that Willard was not executed points in the direction of this song being a cautionary tale for young men who have extramarital sex and then regret it. Best not to sleep with young women or you’ll have to kill them and who has time for that, am I right?

Yeah, I have the jaded eye of a modern woman but it is interesting how seldom these femicide ballads are told from the perspective of the woman on the other end of the beating stick. Still, the element of punishment also helps the modern listener, even if the punishment is seen as little more than the natural end to trusting a loose woman. However, in another murder ballad that is directly based on an actual, verifiable murder, the male aggressor does not receive much sympathy.

I first learned about the story of the 1828 murder of Maria Marten in my early days in the true crime rabbit warren, as well as seeing it mentioned in paranormal books. Maria was an English woman in Suffolk who succumbed to the libidinous charms of one William Corder, a conman and rakish rogue. He was not her first dalliance, as she already had two children born out of wedlock. Maria predictably became pregnant and gave birth to Corder’s child and, you’ll never see this plot twist coming, he agrees to marry her to shut her up. When she pressured him too much he tried to handle the situation in a novel manner – he told Maria they had to leave town quickly and elope because the police were about to arrest Maria for bearing so many children out of wedlock. He spoke of his plan in front of her family, but of course Maria never made it out of Suffolk as Corder took her to a red barn and shot her. He then went on with his life, writing letters claiming he and Maria were happy in London.

However, Maria’s family were uneasy, and her stepmother most of all. She claimed that Maria’s ghost appeared to her and told her that William had killed her and where to find her body. Her stepmother finally got authorities to listen to her and Maria’s body was found exactly where her stepmother said it would be. William Corder was arrested and later executed for her murder. Interestingly, he comes up in my (excruciatingly long) essay about anthropodermic bibilopegy – books bound with human skin – because his court proceedings were bound in his skin and placed on display in a museum in Bury St. Edmond. Corder’s reputation took a harder hit, even though the woman he killed was of loose virtues, because he had behaved as a complete asshole his entire life. One would wonder how much better he would have done had the balladeers been presented with a man with less theft and fraud on his record. This story appears in several ballads, two of which are named “The Murder of Maria Marten” and “The Red Barn Murder.”

Murder ballads of the “romantic variety” fairly infest country music. Waylon Jennings’ “Cedartown, Georgia,” Johnny Cash’s “Delia’s Gone” and “Kate” come to mind but most notable to me is Willie Nelson’s The Red Headed Stranger album. It’s a concept album devoted to the idea of the titular stranger as a murderous drifter with a gun. The album’s killer may or may not have murdered his wife but he definitely killed the woman who tried to steal his horse. “El Paso” by Marty Robbins flips the script a bit, as the killer takes out the man who was his rival for his lovely Felina, but is shot down by vigilantes, only to die in Felina’s arms. Still killed a man but this time the woman survived so that’s something and I’m clinging to it.

We get to see the perspective of the female murderer in some country songs. The trio formerly known as the Dixie Chicks sang a song called “Goodbye to Earl,” explaining why Earl had to die. He was a vicious abuser and deserved the murder the three twangy Furies inflicted on him. Martina McBride’s “Independence Day” tells the story of a woman who burned down the house to kill her abusive husband, told from the perspective of the daughter who understands why her mother did what she did. Interesting how murder ballads wherein the female is the killer are generally killing to avenge or prevent abuse. It kind of reminds me of the now-adage that men fear women will humiliate them while women fear men will kill them. That quote is attributed to many women, but most notably Margaret Atwood, who interestingly features in a short story a doomed woman who sings a murder ballad from the perspective of the woman being murdered. It seems fairly likely that “The Knoxville Girl” influenced this story, as one of the lyrics is:

Oh Willy Willy, don’t you murder me,

I’m not prepared for eternity.

Willie, Willard, the end is the same – a gal upset a man and he had to kill her.

I think Norah Jones’s “Miriam” is very interesting because the murderess is singing to her friend Miriam who slept with her husband. One day when I have more time for research than Oddtober permits, I’d love to pick this topic back up again and see how many murder ballads are from the perspective of a female killer, and then subsection that into the number of times a woman kills a woman. In fact, this is a topic that requires the sort of deep dive that I would need to devote a month of research to handle properly so please know this discussion is wildly incomplete. I couldn’t begin to catalog all the “boy sleeps with girl then kills her for being such a whore” or “boy loves girl and kills his rival for her hand” songs in folk or country music. And god help me if I try to venture into rock music. Nick Cave’s album Murder Ballads is worth an entry all on its own. But then “I Used to Love Her” by Guns ‘n Roses immediately comes to mind and I sort of hate that song so I sense any further attempts in this vein will spiral into another fifty thousand word OTC entry.

Still, it was interesting finding hip hop and rap murder ballads. One unexpected gem was Plan B’s song about a fictionalized murder victim who fell at the hands of the very real Camden Ripper. “Suzanne,” the woman in the song, was a prostitute who was savagely murdered, and the tone of the song is one wherein Suzanne is a mourned victim, not a nasty girl who got what was coming to her. She was a savaged woman whose screams permeate the song.

This also makes me wonder how many songs there are out there that focus on serial killers. I stumbled across one such musician and her body of work and plan to discuss it in the part two of this discussion because it straddles the line between just serial killer storytelling and borderline hero worship of such killers. Frankly, the “killer as a folk hero” strain of murder ballads is also heavy with femicide but ultimately is a bit more entertaining. Come back tomorrow and see what I dug up, and until then, if you have a favorite murder ballad that falls into the “kill her because she’s a slut” and “star-crossed lovers doomed to die” categories, or subverts them as the Plan B song above does, please share in the comments.