Yep. Anthropodermic bibliopegy. That’s the technical term for books bound in human skin.

I decided to write this article after I stumbled across five mentions of anthropodermic bibliopegy in a 48 hour period. I took that as a sign that books bound in human skin was a topic I needed to discuss here – synchronicity isn’t something I really put much faith in but I wager that the average person might think it a sign if she just happened upon several references to such an arcane subject. It didn’t hurt that I found books bound in human skin extremely interesting. Also, as I read about these books, I found myself wishing there was a master list and discussion of the more famous examples of anthropodermic bibliopegy, and who better to compile a long, wordy list than me? And here we are!

Because of my interest in true crime, I knew that there were instances wherein court records were bound in the skin of executed criminals. I was also familiar with a few examples of anthropodermic bibliopegy in pop culture, notably the Evil Dead films. But given the morbidity of the subject, I was surprised at how little I knew about these books, real or fictional. Books, creepy things, unsettling representations of the dead – you’d think I would have been all over this topic by now.

As I read about books bound in human skin I noticed that there was a surge of articles on the subject in the spring and summer of 2014. Harvard University tested three suspected examples of anthropodermic bibliopegy in their collections and only one was genuinely bound in human skin, the skin from a woman who spent her life in a mental asylum. Those tests spurred a media interest in anthropodermic bibliopegy, and an interest I am deeply appreciative for because otherwise I don’t think research into the topic would have been so easy. Though several sources I read insisted that the practice of binding books in human skin was once an accepted practice, it was not a common practice and more or less ended in the late 19th century. There are very few of these books that remain in museums and libraries.

Though the bulk of the remaining examples of anthropodermic bibliopegy are from the 18th and 19th centuries and primarily from Europe, claims that skin was used for book bindings date at least as far back as the 13th century. Prior to the development of precise scientific testing to determine skin origin, experts determined origin of skins via microscopic analysis. Physicians and museum curators observed patterns in cuticles and tiny hair remnants left in pores after the tanning process and used those patterns to determine the animal that provided the skin. Many books claimed to be bound in human skin were identified as such by using microscopic analysis – not many have been subjected to more modern tests. One of best tests for animal origin of tanned skin is peptide mass fingerprinting, which analyzes the proteins left in tanned skin. Those proteins point to the animal the skin was taken from and though at times the protein markers show simply that the skin was taken from primates, it can be assumed that those primates were humans. Monkeys were not thick on the ground in Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries. At least one book, which I will discuss, that was considered one of the best examples of a book bound in human skin, was proved to be bound in sheep or cow hide after peptide mass fingerprinting. I suspect that a significant number of books authenticated as human skin using older, microscopic methods would not be authenticated as human if tested using peptide mass fingerprinting (and that method cannot determine who specifically donated skin as the tanning process destroys DNA).

The Mütter Museum of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia currently has the largest collection of books bound in human skin in the USA, counting five total volumes, three of which were bound in skin from a single donor. All five have been tested according to modern standards and the bindings have been proven to be of human origin. The Mütter Museum has formed a team to try to create a comprehensive list of all the examples of anthropodermic bibliopegy, encouraging institutions to test all the books in their collections that are alleged to be bound in human skin:

Most institutions the team has worked with are keeping quiet, however. During her presentation at Death Salon, Rosenbloom did share the aggregate results so far: Out of the 22 books the group has tested, 12 have been found to be made out of human skin. According to one of Rosenbloom’s slides, the remainder were found to have been bound with “an assortment of sheep, cow, and faux (!) leather.” The team has also identified an additional 16 books that they have not yet tested—and is working to locate more.

I have to think that there are likely some undiscovered examples of anthropodermic bibliopegy in private collections, but I think that if one of the largest known collections of books bound in human skin has only five books, perhaps the custom of binding books in human skin was indeed less common than some of the sources I consulted seem to think it was.

As I read about anthropodermic bibliopegy, the topic fell neatly into several categories: criminals whose skin was harvested after their executions; skin used from people who could not or did not give meaningful consent to have their skin used after their deaths; voluntary skin donors; books proven not to be bound in human skin after peptide mass fingerprinting; and representations of human skin-bound books in pop culture.

I found interesting a lot of the squeamishness and revulsion people feel for books bound in human skin. Often it seemed as if this revulsion was rather selective, given some of the truly macabre museum exhibits that exist, from the entirety of the Mütter Museum to the visually disturbing but excellently bizarre flayed Musee Fragonard exhibits. It seems strange to be upset about a book bound in human skin when you can see dissected bodies on display in medical museums, bodies that were often curated without the consent of the person when he or she was alive. However, the longer I read about this topic, the more I found myself feeling a bit uneasy about some of the examples of books bound in human flesh. I am unsure if this is a 21st century mentality. Perhaps it is because I am accustomed to patient/family consent in medical and funeral procedures. Or maybe my discomfort is linked with my identification with the underclasses who ended up providing most of the skins used to bind books. I wonder if others who immerse themselves in this topic find themselves growing a bit indignant about the fates of some of the people who provided their skins.

Please note that I exercised some discretion that may seem offensive since I am not an antiquarian, book binder or scientist, but you will find that there are some “authentic books” that I think are unlikely to be bound in human skin. Sometimes I left the books with questionable authenticity in the “real” sections and sometimes I put them in the “fake” section. Generally the “authentic” examples of anthropodermic bibliopegy that I place in the hoaxes or disproved section are pretty egregious fakes.

Criminals

In the early 19th century, medical colleges and surgeons had a hard time obtaining corpses for dissection, and frequently dissected the bodies of executed criminals. In the process of these dissections, some of the criminals ended up flayed, their skin tanned and used to bind books (and also used in an array of leather goods).

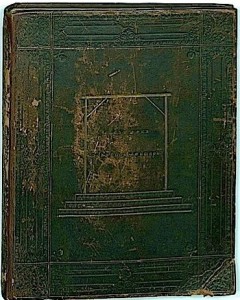

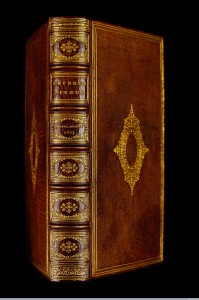

John Horwood developed a fixation on Eliza Balsum (also spelled as Balsam and Balsom) in 1821, after they dated briefly. He stalked her, eventually attacking her by throwing a rock at her (the account in the bound trial records indicates that Horwood bludgeoned Balsum with a large rock but other accounts indicate that the attack consisted of him throwing a rock at her and hitting her in the head). She later died from medical intervention to save her – trepanning, to be specific – but her friends identified Horwood as Eliza’s attacker and he was accused of murder. He stood trial and was found guilty for her murder and was executed. His body ended up being dissected at the Bristol Royal Infirmary, and was flayed in such a manner that there were large enough sections of his skin left that they could be used to bind a book about his case. The book is currently owned by the Bristol Record Office. The book is unremarkable enough to my naked eye – I own books this old, bound in leather, that look much like this volume. However, a keen eye and a working knowledge of Latin gives away this book’s unusual nature. The cover sports a gallows and is embossed with the phrase, “Cutis Vera Johannis Horwood,” which means “the genuine skin of John Horwood.”

This book is part of a museum exhibit in Bristol and is one of the more popular exhibits. As I mentioned above, I found much of the squeamishness about anthropodermic bibliopegy strangely selective, but a librarian at the Bristol museum that houses this book made clear her reservations about the John Horwood tome. Allie Dillon, an archivist at the M Shed museum where the book is kept, found the use of Horwood’s skin for a book binding to be exceedingly cruel:

John Horwood seems to have been quite a vulnerable person and this may have contributed to his actions. It does seem very macabre to cover a book in human skin and it is quite difficult to understand why it was done. It seems quite vengeful to me.

John Horwood’s mental state is largely unknown to us now but reading several sources online leads me to believe that Horwood may have suffered from some form of mental retardation. He was certainly from a poverty-level family who had no chance of paying for a decent defense. Almost as bad as executing a mentally retarded man (a common enough modern practice where I live) is how Horwood’s family was deprived of the body of their executed son and brother. They attended his execution with the sole intention of collecting his body for a proper burial but were denied his corpse by the doctor who was intent on dissecting him. This blog discusses in depth the complete nastiness involved in the use of Horwood’s body after his death. In this case I can see why people would find this book particularly distasteful. And it doesn’t end with the book – Horwood’s skeleton was left hanging in a closet at Bristol University – the rope used to hang him was still around his neck. A distant relative investigating his case found his body and arranged to have him buried next to his father.

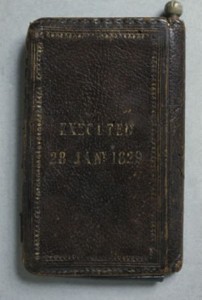

Far less distasteful to me is the notebook made from the skin of notorious grave robber and murderer, William Burke, of Burke and Hare body-snatching fame. In the 19th century, since cadavers for medical research and training were extremely hard to come by, entrepreneurial types took to digging up bodies in cemeteries to sell to universities. William Burke and William Hare got their start in the illegal sale of corpses when they sold the body of a man who had died in Hare’s rooming house. When those around them failed to die off quickly enough for the duo to sell their remains, they began killing people to obtain corpses to sell. Hare was offered a chance to testify against Burke in order to save his own skin, so to speak, and he obliged. Burke was convicted of murder and hanged. After death, his skull was used to demonstrate the finer points of phrenology, he was publicly flayed, and his skin was used to make an array of small leather goods, ranging from wallets, to card cases, to what appears to me to be a sort of early Moleskine-type notebook. It’s not entirely clear how his skin ended up being used in leather goods because it doesn’t appear as if any of it was earmarked for such use. Rather, portions of his skin went missing after the public dissection and later the leather goods showed up – it is not known who tanned Burke’s skin or used it for these items, and as I read about it I wondered if this was really Burke’s skin at all. Not enough evidence exists either way and I could find no evidence that these leather items have been tested. Burke’s execution date of January 28, 1829, is embossed on the front of the little book and that bulb you see extending upward on the right is the top of a pen – there is a slot inside to hold writing implements. This little book is on display at the Surgeon’s Hall Museum in Edinburgh.

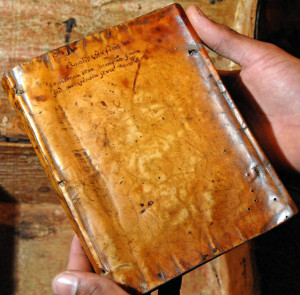

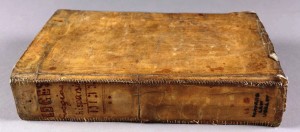

One of the stranger books bound in the skin of a convicted criminal is A True and Perfect Relation of the Whole Proceedings Against the Late Most Barbarous Traitors, Garnet a Jesuit and His Confederates, which is bound in the tanned skin of Father Henry Garnet, who was convicted and executed for his role in the Gunpowder Plot against the British Parliament in 1605. That Father Garnet’s face is somehow visible across the front gives this book a creepy edge though the face isn’t as clear to me as it is to others. Father Garnet’s public execution and flaying was also a bit much for my modern tastes because the good priest didn’t actually play a part in the Gunpowder Plot. He simply heard the confessions of those who were involved and evidently that was enough to condemn him as a traitor.

This blog brings up some interesting points about the Father Garnet book. It was bound in 1606, and there are very few examples of anthropodermic bibliopegy that occurred prior to the French Revolution – this book pre-dates the revolution by over 170 years. Moreover, a close look at the actual leather shows it to be different than the appearance of other examples of books bound in human skin. It’s rather glossier, with a very fine grain and missing are the pores one sees in examples of anthropodermic bibliopegy that have been determined to be genuine after peptide mass fingerprinting tests. Moreover, there is no record of Garnet’s skin being used in such a manner, a similar problem with the records surrounding William Burke’s skin. And of course, the face on the cover of the book is open to all kinds of interpretations but it seems mostly to be leather discoloration and the human tendency to see faces in wooden floors, burnt toast, and foxing in books. This tiny book – 4 inches by 6 inches – sold for $11,000 in an auction in 2007 and if I were the owner I’d spring for a peptide mass fingerprinting test, though I don’t think he or she can get a refund if it turns out to be sheep skin.

William Corder’s court proceedings were bound in his skin and his case was the sole example of real anthropodermic bibliopegy I was aware of before I began reading about the topic, a bit of knowledge from my time as a minor expert in murders. William Corder impregnated an Irish girl named Maria Marten. He convinced her he wanted to marry her and lured her to her death, killing her and burying her inside a red barn, causing the case to be referred to as The Red Barn Murder. Maria’s stepmother had recurring dreams of her buried at the Red Barn and eventually authorities investigated and found her remains. Corder was tried for her murder, convicted and then executed. As done with many executed criminals, his body ended up dissected in a medical school and his skin was preserved and used to bind the court proceedings from his trial. The book is on display at the Moyse’s Hall Museum in Bury St. Edmunds, Suffolk. George Creed, the surgeon who flayed him, left this inscription in the book:

The Binding of this book is the skin of the Murderer William Corder taken from his body and tanned by myself in the year 1828. George Creed Surgeon to the Suffolk Hospital.

And just to get in that extra dose of historical creepiness, the book is on display alongside Corder’s scalp and death mask.

So many of the books bound in human skin are not volumes meant for the ages, but George Cudmore’s skin at least was used to bind a copy of John Milton’s poetry. George Cudmore was a rat catcher who was executed for poisoning his wife, at the urging of his mistress. It’s interesting to me that Cudmore managed to have both a wife and a mistress given his overall appearance and demeanor. He was a hunchback and short, and he was clearly of a vengeful nature – when he was convicted he demanded that his mistress be forced to watch him hang (a request the judge granted!). He was executed in 1830 but the book of Milton’s poems was not published until 1852. It is unclear how an Exeter bookbinder came to have Cudmore’s skin, but a certain Mr. Clifford bound the Milton volume in his hide. The only reason anyone believes this book to be bound in Cudmore’s skin is due to an explanation inscribed in the book – it could very easily be another hoax. The book is kept at the Westcountry Studies Library, and I can’t find any evidence that the book was subjected to modern tests to see if it is indeed bound in human skin.

Samuel Johnson, noted lexicographer and blowhard, compiled a definitive collection of English words in 1755, A Dictionary of the English Language. In 1818 a man named James Johnson was executed in Norwich and for some reason his skin was used to bind a copy of the dictionary. No one knows why. I guess there were so many executed criminals that their tanned skins were just crying out for a legitimate use.

On the site Literary Curiosities, I found a very interesting fact about extant books bound in human skin – the majority of them come from French aristocrats executed during the French Revolution.

A French publisher once brought out an edition of Rousseau’s Social Contract bound in the skin of aristocrats guillotined during the Reign of Terror following the French Revolution. Other publishers in France at the time evidently took advantage of the same situation, for a high percentage of books now extant covered in human skin are in French.

An edition of The Rights of Man and copies of the French Constitution were also proven to be bound in human skin. The Carnavalet Museum in France has a copy of the French Constitution bound in human skin dyed green. The French don’t mess around. I’ve often laughed at Americans who sneer at the French and consider them weak. The French are a bunch of violent and dangerous savages kept at bay through a veneer of civilization and a socialist welfare state. The same can be said for Germany and god help us all if either country adopts American-style “I got mine, eat dirt asshole” free market capitalism. Because we all know how that will end up: Guillotines west of the Rhine, jack boots and beer hall putsches east of the Rhine. (Read this with tongue in cheek or leave me angry comments, whichever works for you.)

Unwilling or unwitting skin donors

Generally the prisoners whose skin was used to bind books did not volunteer to be posthumously flayed for the purpose, but given the overall cruelty in the judicial and penal system in 18th and 19th century England, it’s not wholly unexpected that the bodies of dead criminals would be shown little sentimentality or respect. Being used in medical schools or being turned into leather goods, while not always the end result of capital punishment, was not surprising either. You do the crime, you serve the time, as it were.

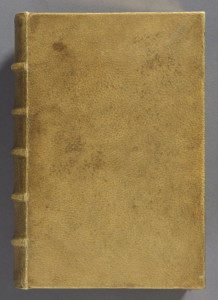

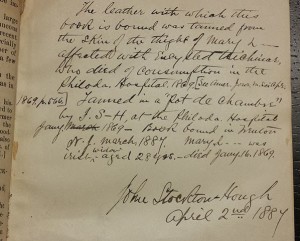

But if using the bodies of dead criminals to bind books seems callous and macabre, doubly so was the use of bodies of mental patients or people whose only crime in life was to die sick, poor or alone. The book that spurred the renewed interest in anthropodermic bibliopegy in spring/summer 2014 is unremarkable to look at, though if you click the image to see a larger version, you will see, very clearly, pores and blemishes that give pause when you remember this book was bound in human skin. When subjected to tests, it was proved that a book from Harvard’s Houghton Library, was indeed bound in human skin, giving credence to the explanation penned inside the book, that the book was bound in the skin taken from the corpse of a woman who died in a mental hospital and whose body was unclaimed.

The book, Des destinées de l’ame by Arsène Houssaye, is a book that muses on “the nature of the soul and life after death.” The subject matter lends itself well to feeling a bit distressed regarding the origin of the book’s leather. From the same atlasobscura.com article linked to above:

[Des destinées de l’ame] is bound in the skin of an unwilling participant, an unnamed woman who died of apoplexy or a stroke while confined to a mental institution. The author, Houssaye (1815-1896), presented this copy of the publication to his friend, a medical doctor and book collector named Ludovic Bouland (1839-1932).

It was Bouland who chose to use the skin of a deceased patient, whose body had remained unclaimed by friends or relatives.

Bouland inscribed the following in the book:

This book is bound in human skin parchment on which no ornament has been stamped to preserve its elegance. By looking carefully you easily distinguish the pores of the skin. A book about the human soul deserved to have a human covering: I had kept this piece of human skin taken from the back of a woman. It is interesting to see the different aspects that change this skin according to the method of preparation to which it is subjected. Compare for example with the small volume I have in my library, Sever. Pinaeus de Virginitatis notis which is also bound in human skin but tanned with sumac.

The sources about this book were a bit garbled, indicating that Houssaye wrote the above inscription when it was clearly Bouland, and I think this confusion caused people to overlook something implicit in Bouland’s inscription. He already had the piece of skin when he was given this book as a gift from Houssaye. He had flayed the woman and preserved her skin before this book was even on his radar. He just had a piece of skin around the house and used it. Bouland actually did bind other books in skin – perhaps he just liked to be prepared, but it’s a bit unusual to my modern mind to imagine someone flaying a woman who died just because one day he may want to bind a book in human skin. This book has been of particular interest to dermatologists who have been able to observe the durability of skin and how the tanning process affects human skin. Look at the pictures of the book in this article – this book does look disturbingly human.

Ludovic Bouland also bound a 17th century volume about female anatomy in the skin of another woman. The book is:

…a collection of gynaecological essays by various authors, beginning with Séverin Pineau’s treatise on virginity, pregnancy and childbirth, De integritatis et corruptionis virginum notis. Marcellin Lortic, a distinguished Paris binder, bound Pineau’s treatise using a piece of woman’s skin that had been tanned with sumach. The binding was done at the request of Ludovic Bouland (d. 1932), a doctor from Metz, who trained in Strasbourg in 1865 and practised in Paris. Inserted at the front of the book is a note by Dr Bouland, explaining he felt it deserved a binding to match its subject matter and that he had obtained the piece of skin from the body of a woman who had died in the hospital at Metz where he had been working as a medical student.

Bouland’s clearly a man whose mind is foreign to me but it’s a bit unsettling that he felt the book deserved the skin rather than that the woman whose skin he pocketed deserved to be memorialized. Though, in all truth, I know little about the volume in question. Maybe it is deserving of the skin of a forsaken woman. This book is currently housed at the Wellcome Library.

Dead women seem to make up almost all of the non-criminal unwilling/unwitting donors. Medical students evidently skinned dead women and sold their skins to erotica publishers in the 19th century. Notably, a copy of Justine et Juliette by de Sade was bound in the breasts of one such forsaken woman. There are reports online that the cover of this de Sade tome sported a nipple, but I could not find a photograph of the book. From what I have been able to determine, the de Sade book did not have a nipple on the cover and the belief that it did comes from some of the garbled data that seems to plague this topic. I’ve found several sources, like this one, that says that de Sade’s book L’eloge des seins features a human nipple on the cover, and from there it’s a short hop to Justine et Juliette being bound in breasts. But don’t hop, because L’eloge des seins was not written by de Sade. The so-called “Nipple Book” is actually a copy of L’eloge des seins by Claude-François-Xavier Mercier, and it was bound with skin from breasts, and a visible nipple appears on the cover. This is all the more French because the title of the book, translated into English, is The Praise of Women’s Breasts. But all of this is speculative and possibly in the realm of hoaxes because I could not find a picture of either book and, until both are shown to have been subject to peptide mass fingerprinting, these stories of boob books sound a bit fantastic. Still, it has to be said that if you were going to bind a copy of a de Sade book in a woman’s skin you’d want to use breast skin. Or maybe pieces from the derriere.

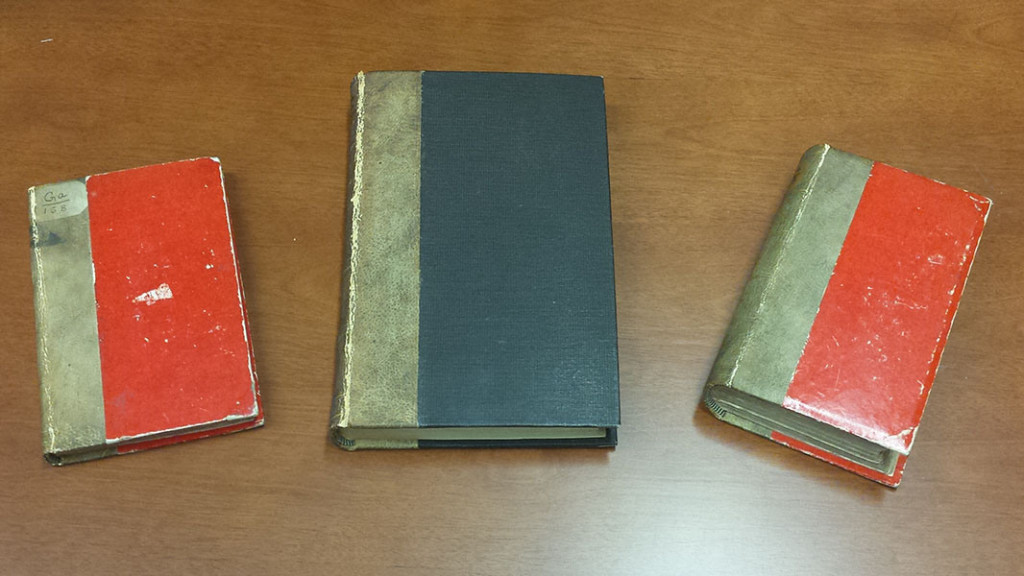

From the fantastic to the all too real, the Mütter Museum has at least three examples of a woman’s skin being used after her death without any real permission from the woman before she was flayed. Though the doctor who autopsied her and flayed her thigh didn’t use her full name in the case study he wrote about her or in the inscriptions he wrote about her in the books he used her skin to bind, Dr. John Stockton Hough gave enough identifying information that intrepid historians were able to track down the “donor”: her name was Mary Lynch, and she had been admitted to Philadelphia General Hospital with a case of tuberculosis. She was admitted during a warm summer and her relatives brought her pork products to eat, ultimately giving her a terrible case of trichinosis, an area of interest for Dr. Hough. He autopsied her after her death and, for reasons that are not really clear to anyone, decided to cut off a piece of skin from her thigh and used it to bind three books. Maybe he did it because he was a bibliophile? Maybe because Mary had the worst case of parasites he had ever seen and he just had to remember her? Unsure, but he did, indeed, flay her skin, tan it and use it to partially bind three books.

The three titles Mary’s skin was used to bind are:

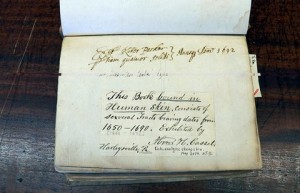

Speculations on the Mode and Appearances of Impregnation in the Human Female…published in 1789; Le Nouvelles Decouvertes sur Toutes les Parties Principales de L’Homme et de la Femme… published in 1680; and Recueil des Secrets de Louyse Bourgeois…published in 1650. Each of these books deals with female health, conception and reproduction.

At times I wondered if I was being a bit over-sensitive about the habit of some doctors to cut skin from cadavers as if they had some greater right to claim random parts of the female, often impoverished dead, often without any anticipated use for the skin when they took it. Beth Lander, a librarian at the Philadelphia College of Physicians, who wrote the article I link to above about Dr. Hough and Mary, raised similar issues about Dr. Hough’s flaying of Mary Lynch:

The books as objects force us into uncomfortable considerations of the use of human skin in bindings: Was Mary memorialized in these books? If so, why did Dr. Hough keep her skin for nearly 20 years before using it?

Why did Dr. Hough use Mary’s thigh skin to bind books about conception and childbirth? What, if anything, was he saying about Mary, or women in general? Were other people aware of what he was doing?

Does the use of human skin diminish the value of the books as text, and render them nothing more than objects of morbid curiosity?

In Dr. Hough’s case, he did attempt to memorialize Mary by writing about her in his inscriptions in the three books, even as he tried to protect her privacy (though I have to wonder if he hid her last name to prevent living relatives from reacting in anger). She was not hidden from history completely. And her skin was used to bind books about female anatomy. Perhaps Dr. Hough did feel some connection to this young woman killed by parasites, one of his areas of specialty, and he wanted a piece of her skin. But even extending sentimentality to such an act doesn’t really help me understand the compulsion of some medical men to skin patients, especially when there was no revenge/justice motive as there was in flaying executed criminals. I want to believe that Dr. Hough felt some special connection to this woman, that he didn’t skin her just because he could, but that very well could be the case. (And the article Beth Lander wrote is worth reading from beginning to end. In fact, the entire blog, Fugitive Leaves, is worth reading.)

Four of the five books bound in human skin at the Mütter Museum came from Dr. Hough. The book that was not bound in Mary’s skin is a copy of Bibliotheque Nationale. Dr. Hough wrote that the book was bound in human skin but little else is known about the book other than that the skin came from the donor’s back. Despite the fact that Dr. Hough flayed a woman who did not give consent for such a procedure, Paul Wolpe, a bioethicist at UPenn, had this to say about the anthropodermically-bound Bibliotheque Nationale:

He emphasized, though, that with artifacts such as Bibliotheque Nationale, the skin used was not from exploited individuals, such as slaves or concentration-camp prisoners, but often from people of significance to the binder.

Wolpe also went on to say that he believes Mary Lynch’s case to be one of Dr. Hough honoring his dead patient, not one of a rich doctor exploiting a poverty-level immigrant. I hope he’s right.

So while we are discussing the books at the Mütter Museum, let’s have a look at the sole book that did not come from Dr. Hough’s collection. This book came from a different doctor – Dr. Joseph Leidy, another Philadelphia medical man. His book bound in human skin was not as well-documented as Dr. Hough’s were. Dr. Leidy’s contribution to the Mütter Museum’s collection is a copy of An Elementary Treatise on Human Anatomy. Inscribed inside the book:

The leather with which this book is bound is human skin, from a soldier who died during the great Southern Rebellion.

Dr. Leidy was a surgeon for the Union during the Civil War, so that is likely how he obtained the skin from the soldier. I placed Leidy’s book here in the “unwilling” donor section because given the behavior of other doctors during this time, it seems unlikely Dr. Leidy asked the dying soldier if he would consent to having skin removed in order to bind a book.

Jacques Delille translated Virgil’s Georgics into French and was renown as an excellent translator. A copy of his Georgics translation was bound in his own skin. There’s not a lot of back story to this particular book because we don’t really know how his skin was obtained for the purpose. After Delille died, he must have been left unattended for a good while as he lay in state because someone managed to slip in undetected and remove a portion of his skin. Or a funeral attendant received a nice bribe to look the other way. Still, the mind fairly boggles.

This next book bound in human skin is less a mind-boggler than it is a head-shaker. From Daniel K. Smith’s article on anthropodermic bibliopegy in The Morbid Anatomy Anthology, I found this bizarre and disturbing example of anthropodermic bibliopegy 1. In the collection at the Clendening History of Medicine Library in Kansas City sits one of the more on the nose book bindings, even more on the nose than binding books about female anatomy in the skin of random women. A 17th century book on the pituitary gland – Exercitatio anatomica de glandula pituitaria – ended up being bound in the skin of circus giant. Dr. Charles Humberd, owner of the book, somehow got his hands on the skin of an 8’6″ tall giant who traveled with the Ringling Brothers Circus. An inscription on the front end page says:

De luxe binding of / human skin from the / circus giant “Perky.”

Humberd’s name rang a bell with me. I had read about him in Freak Show by Robert Bogdan. Humberd was sued by the world’s tallest man, Robert Wadlow, for libel. Humberd showed up randomly at the Wadlow home one day, Wadlow refused to be examined, and based on that brief visit Humbert published an entire case history about Wadlow 2. Humberd evidently had a strong, bordering on fanatical interest in people who grew to enormous heights due to pituitary illnesses, collecting their shoes and other personal possessions. Given the nature of his obsession with giants and his relative lack of ethics, I can believe both that he could very well have had the skin of a giant and that Exercitatio anatomica de glandula pituitaria may not be bound in human skin at all. What makes me lean toward this being another hoax is the fact that no one seems to know who “Perky” might be – even people devoted to the topic are unclear on Perky’s identity. I feel myself with the urge to read all I can about Humberd – he sounds like an obsessive weirdo who was also a genius. Maybe one day I’ll find out who Perky was (I’ve seen several places that wonder if Perky was Clarence Perkins, but Clarence Perkins doesn’t appear on any list of circus performers I’ve found online and doesn’t come close to reaching 8’6″). As of what I have read online, this book has not been subject to peptide mass fingerprinting.

There’s a sort of colonial approach to book binding with human skin that I could initially dismiss but became more and more evident as I read about anthropodermic bibliopegy. This can be seen especially in a book that is kept at the John Hay Library at Brown University. A copy of Andrea Vesalius’ De humani corporis fabrica, a beautiful 16th century text full of detailed drawings of human dissection, was bound in human skin and presented to King Leopold II of Belgium. I cannot find anything about the donor of the skin and when that is the case I tend to lean toward the skin being less donated than harvested without consent, but it is interesting that this book bound in skin was presented to this particular King. From the article in The Morbid Anatomy Anthology:

[this book] was bound for King Leopold II of Belgium, who was at the time directing the mass murder of millions of Africans in the Congo. Under the guise of stopping the slave trade in the Congo, he sent European adventurers and mercenaries to the unmapped African interior, where they killed, enslaved, tortured, raped, and maimed in the most brutal ways while harvesting ivory and later rubber. Vesalius’s bold and daring work had formed the art of surgery out of what was at the time more butchery than treatment – and here it was, gifted to one of the greatest butchers of the nineteenth century.3

Yeah. It got real dark real fast, didn’t it.

I am unsure if the donor in the next example volunteered his or her skin, but in the absence of clear willingness, I assume a donor was involuntary. This book is also in the John Hay Library at Brown University, and may be one of the few relatively mainstream novels ever to be bound in human skin. The title is Mademoiselle Giraud, ma femme, written by Adolphe Belot in 1870. The book sounds like a steamy potboiler – a man discovers his wife is a lesbian and becomes completely unhinged. From The Morbid Anatomy Anthology article:

Handwritten on the front flyleaf of the John Hay Library’s copy is “Bound in human skin/S.B.L.” and on the back “Genuine Human Skin” in the same hand. The library also holds a letter written by Sam Loveman of Bodley Book Shop further attesting to the book’s authenticity. 4

Not sure if Sam Loveman’s word is enough to consider this a closed-case regarding this book, but whether or not this book is bound in authentic human skin, Sam Loveman was a friend of H.P. Lovecraft and this book may have been inspiration for details in one of Lovecraft’s stories.

There are extant examples of The Dance of Death bound in human skin. A British bookbinder named Joseph Zaehnsdorf discussed in a letter how he was forced to split in two a piece of human skin to make it large enough to bind a collection of Hans Holbein’s Dance of Death woodcuts. This particular Dance of Death has an interesting distinction. Again, from The Morbid Anatomy Anthology article:

This binding is plain and unadorned with a remarkable exception: human hair was used as headbands, and a few strands remain.5

I was unclear on what a headband meant in terms of bookbinding and found this tutorial that explains it well. I have so many questions. Like did the hair and the skin come from the same donor? And if not, why would anyone mix body coverings in such a manner?

Again, in Smith’s article in The Morbid Anatomy Anthology, I was confronted with yet another strange volume that raised some odd questions that I had to seek answers for online. The Grolier Club in New York boasts a book bound in skin, a collection of poems written in the 16th century. Le Traicte de Peyne translates to “Treatise on Suffering” and a 19th century introduction explains that the volume consists of allegorical poems as written by three penitents (the description on the Grolier’s Club website lists the subject of this book to be pain and masochism) 6. This was not a book that was ever published and I wonder how much skin these Parisian bookbinders had just lying around that they didn’t flinch at binding a book in human hide a collection of poems that was never submitted for publication. It makes me wonder how many books there are like this still in private collections, books written for a particular set of eyes only, never intended for distribution, bound in skin for reasons that were never shared.

One of the funnier stories I read about anthropodermic bibliopegy comes from Dr. Caroline Archer’s article for Typographic Hub, “Print’s Macabre Side”:

In My life with paper, the Ohio-born master printer and book designer Dard Hunter recalls being hired by a young widow to bind a volume of letters dedicated to her late husband using his own skin. The widow remarried and Hunter wonders whether her second husband saw himself as volume two, wryly concluding: ‘Let us hope that this was strictly a limited edition.’

Since I am unsure if the husband volunteered his skin, I am placing this book in the “unwitting” category.

Voluntary skin donors

One of the more famous voluntary skin donations was used to bind a book on astronomy. I am wholly unfamiliar with the works of Camille Flammarion and that seems a grave oversight given some of the odd claims the French astronomer made, among them that Halley’s comet was going to demolish the Earth and a sort of proto-type of the ancient alien theories wherein he was certain that Martians had communicated with the Earth in the distant past and shaped current civilizations. He was also a fan of the “Ezekiel’s Wheel was totally a spacecraft” theory. In spite of his odd ideas, or perhaps because of them, a French countess who was a fan decided that after she died she wanted to send him a swathe of her skin to use to bind one of his books. Actually, from some descriptions she was infatuated with Flammarion, though the two never met, and it was a sort of erotic gesture on her part. This woman also had a tattoo of Flammarion somewhere on her body, though one presumes it was not on the part of her skin she contributed for the book binding (and a good thing, too, because can you imagine receiving a patch of skin with your own face tattooed on it in the mail?). She died young from tuberculosis and was flayed posthumously. Flammarion was touched by the gesture and used her skin to bind the first copy of his book called Terres du ciel in 1882. Strangely, despite an unseemly amount of time looking, I cannot find a picture of the actual book in question, though dozens of articles reproduce a photo of the manuscript without any visible binding. The book currently resides at Flammarion’s observatory in Juvisy.

Not all voluntary skin donors are anonymous. James Allen (real name George Walton), was a famous highwayman in the 19th century. During his career, he evidently only ever had one person resist him during an attack and Allen was so impressed with that act of courage that he made an unusual request:

On facing the gallows, Walton stipulated a copy of his memoirs be bound in his own skin and given to John Fenno, a man whom Walton had attempted to rob on the Massachusetts Turnpike. Fenno had so impressed Walton by bravely resisting the robbery attempt, weathering a gunshot wound, and assisting in bringing the highwayman to justice that Walton honoured his victim with this macabre anthropodermic bibliopegic gift. After Walton’s execution the book was delivered to Fenno whose relatives eventually donated it to the Boston Athenaeum, where it remains today.

(Note that sources vary on when it was that Walton decided to donate his skin for bookbinding. The above quote indicates that Walton/Allen faced a death sentence, implying that he was executed. However, other sources, notably Daniel K. Smith’s article in The Morbid Anatomy Anthology, say that Walton was sentenced to a prison term and died in prison, asking the warden to write down his biography and bind two copies of it in his own skin 7. So many of these books have different stories about them.)

It’s a simple, short book, with the phrase Hic liber Waltonis cute compactus est embossed across the front (Latin for “This book is bound in Walton’s skin”). The Boston Athenaeum is pretty tight about reproducing images of their books and have not replied to my request to use a picture of the book in this article, but they have such a great scan on their site that it’s hard to complain.

Have a look at the large-scale photo available on the Athenaeum’s website – it is creepily skin-like, if that doesn’t go without saying. The pore size, the appearance of the skin – it really appears very human-like in comparison to sheepskin bound books from the same time frame. The entirety of the book is also available via the above link and can be downloaded.

I wonder how many books are bound in the skin of besotted women because another extant example comes from such a woman. The mistress of the French novelist Eugène Sue left instructions in her will that a copy of one of Sue’s novels be bound in her skin, and that instruction was carried out. Sue’s novel, Vignettes: les Mystères de Paris, was bound in her skin. Sadly, the book doesn’t seem to have much cachet – in 1951 the book was sold at a French bookstore for the modern equivalent of $29. If Mr OTC skins me posthumously, I hope a book bound in my carcass fetches a bit more than the equivalent of a date night at Olive Garden.

Strangely, this example from a voluntary donor was the creepiest book of them all for me. I can’t find pictures of it or more information than is available in this atlasobscura.com article, but this brief mention is still worth discussing. An edition of The Harvard Crimson in 1933 mentions a small book called Little Poems for Little Folk:

[the book] was bound in the skin of a donor who remained happily alive and healthy after the removal of 20 square inches of skin from his back. The book was privately owned; the book’s current whereabouts are unknown.

Wow. I have to wonder what was so important about a book of poetry for children that a person was willing to have his skin removed while he was alive in order to bind it. I really want to know more about this book. I sort of want to own it.

Legends and Hoaxes/Disproved Claims

For years Harvard suspected they had some examples of anthropodermic bibliopegy – Des destinées de l’ame being one of them, and testing proved that volume was indeed human skin, as discussed above. However, one of the books suspected of being bound in human skin proved to be fake. Practicarum quaestionum circa leges regias Hispaniae by Juan Gutiérrez, bound at some point during the 17th century, contained this bizarre inscription on its last page:

The bynding of this booke is all that remains of my dear friende Jonas Wright, who was flayed alive by the Wavuma on the Fourth Day of August, 1632. King Mbesa did give me the book, it being one of poore Jonas chiefe possessions, together with ample of his skin to bynd it. Requiescat in pace.

Given my relatively crappy knowledge of African history, I feel no shame in admitting that I have never heard of the Wavuma tribe or King Mbesa, but lucky for me this guy in the comments in the Harvard law blog I linked to above has heard of both and had this to say:

It looks in any case as if the Wavuma are a Ugandan tribe with which the British first made contact in the 19th century. (Which seems as if it would have made the inscription suspect even before running the tests.)

Since the tests showed the binding of the book not to be of human origin, it’s safe to say this was a hoax, though the purpose behind it remains unknown. As I read about anthropodermic bibliopegy, it was interesting to see how many articles that pre-dated the tests in 2014 discuss the memorial dedicated to poor Jonas Wright in the form of a book made from his skin, likening the book to the mourning jewelry Victorians would make from the hair of the dead. When reading about this book, check the dates of the articles – this book is often mentioned as being an ironclad example of anthropodermic bibliopegy but it has indeed been proven not to be bound in human skin.

Juniata College in Pennsylvania believed they had a skin-bound book in their collection and the testing Harvard did on their suspected examples of anthropodermic bibliopegy inspired the college to test their own. The volume, Biblioteca Politica, is a collection of Latin essays, published in 17th century France. Inscribed on a front page is an assertion that the book is bound in human skin, but testing in 2014 at Harvard showed the book is actually bound in sheepskin. Though this may be a blow to the college, it may be a boon for librarians because the book had become a popular morbidity among the students, who flowed into the library asking to see the book every semester.

Though no examples ever emerged of anthropodermic bibliopegy from Nazi concentration and death camps, misuse of Jewish skin did happen during the Holocaust. There are extant examples of Nazi prisoners who were skinned after death, mostly skin with tattoos. However, there is no proof to the rumors that Ilsa Koch bound photo albums in Jewish skin or that there were copies of Mein Kampf bound in human skin. History is rife with examples of conquerors flaying their enemies or victims and displaying their skins in some manner – in this grisly regard, Nazis had plenty of company. But just like the myth of the lampshades, the idea that Nazis used human skin to bind books is not based in fact.

The Morbid Anatomy Anthology article mentions briefly that the Newberry Library in Chicago has a book with the inscription:

Found in the Palace of the King of Delhi, Sept. 28 1857, seven days after the assault James Wise MD/Bound in human skin.8

This particular book piqued my curiosity. What assault? What is the book? Who what when where and also how? Evidently the book is The Chronicles of Nawat Wuzeer Hyderabed and there is little proof that the book is indeed bound in skin.

I found out a lot about this book in an unlikely place: a Q&A page on the Newberry Library website for Audrey Niffenegger’s book, The Time Traveler’s Wife. The library plays a part in Niffenegger’s book, and people have wondered if there is indeed a book bound in skin in the library.

The book was owned by John M. Wing, eccentric Chicago publisher, book collector, and benefactor of the Newberry’s Wing Foundation on the History of Printing. There is no information as to how he came to possess the book. The book has two inscriptions on the first leaf of the volume: the first, signed by James Wise, M.D. refers to the Sepoy Mutiny, the siege in which the book was allegedly taken.

The library staff is almost certain the book is not bound in human skin:

The “human skin” question led librarians to the Newberry’s conservation lab, where the staff made several observations of the binding material under a microscope. Comparisons were made with new and old calf, goat, and sheep leathers. It is the opinion of the conservation staff that the binding material is not human skin, but rather highly burnished goat.

I had to include this book in this very long survey of anthropodermic bibliopegy when I read the phrase “highly burnished goat.”

Though this book has not been proved to be a fraud, I have a difficult time believing El Viaje Largo by Tere Medina is bound in the skin of a willing donor, though it appears on several top ten lists of creepy books. The book of erotica was published in 1972, and a copy evidently was bound via a tribal use of human skin. Inscribed in the book in Spanish and English is the following:

The cover of this book is made from the leather of the human skin. The Aguadilla tribe of the Mayaguez Plateau region preserves the torso epidermal layer of deceased tribal members. While most of the leather is put to utilitarian use by the Aguadillas, some finds its way to commercial trade markets where there is a small but steady demand. This cover is representative of that demand.

Even without peptide mass fingerprinting, I think we can safely say this story is questionable at best. Various sources with more cachet than top ten list sites and Pinterest state that there are no known 20th century examples of anthropodermic bibliopegy, so that lends some credence to my knee-jerk response that the story behind this book is a load of pants. Also I encourage anyone who reads here to search for facts about the Aguadilla tribe in the Mayaguez Plateau region and if you find anything at all about current skinning of the dead in Puerto Rico, let me know and I’ll edit this entry. In fact, information about any Aguadilla native tribe anywhere would be helpful because the native tribes in Aguadilla and Mayaguez were the Taíno tribe. I think this was a nice story created before the Internet came to make it hard to pull off such nonsense. There are pictures of the actual book online but I didn’t put one in this article because they are all quite blurry.

Another book that I have no proof is not bound in human skin but suspect is not comes from the Cleveland Public Library, which claims to have a copy of the Koran that was allegedly bound in the skin of a devout Muslim who asked to be flayed and tanned posthumously. An inscription is the only proof that the book is bound in human skin:

On a page inside, a note in faded pencil claims that Professor Wilson of Cambridge confirmed it was likely bound in human skin, and that it belonged to East Arab Chief Bushiri ibn Salim. It’s a deep red, chipped near the binding. It feels like leather — which, I guess, it is. Human leather. The skin is believed to either belong to Bushiri or someone he killed.

On its face this one seems unlikely. Devout Muslims frown even on cremation – it’s hard to imagine a devout Muslim (or any devout member of any Abrahamic religion) asking to be flayed posthumously if they won’t even consider being rendered into ashes. This particular example of potential anthropodermic bibliopegy caused some upset in part of the Muslim community when it appeared in assorted news articles online. In January 2006 Islamic Community Net contacted the Cleveland Public Library to challenge the notion that any Koran could be bound in the skin of a Muslim true believer. The library responded:

Hello — my name is [redacted], Head of Fine Arts & Special Collections. In regards to the article, if you read it carefully the sentence clearly states that the “Quran that MAY have been bound in the skin of its previous owner” is the best verification that has been documented with the item when the library acquired it decades ago. The AP was not incorrect in its statement. We are just not absolutely sure since there is no way to test it.

I redacted the name of the woman who sent the reply because she gets threats from disturbed people accusing her of staging a “blood libel” hoax against Muslims every time she discusses this Koran and I don’t want to add to her burden with this article. Hopefully she and the Cleveland Library can get this book tested sooner than later because if it can be shown not to be bound in human flesh, which I definitely doubt it is, it would make the librarian’s life a lot easier and it would calm those believers who think that lies were made up about their religion specifically to defame them. If this book has been subjected to peptide mass fingerprinting since the brouhaha in 2006-2007, I can find no evidence of it. As for it being a deliberate attempt to tarnish Islam, if you read the whole of this article to this point, you will see that this is a topic fraught with frauds that demean everyone from Puerto Ricans to the entire English penal system to sufferers of pituitary diseases. Of all the things to lie about, a human skin-bound Koran is not the most direct way to defame Islam. But if I were the librarian in question I would encourage testing for this book post-haste for it mostly likely is a fraud and should be declared so if it is.

In Pop Culture

I think most lovers of horror fiction know about H.P. Lovecraft’s Necronomicon, a magical text . The first mention of this book appears in Lovecraft’s “The Hound.” However, that story, according to Smith in The Morbid Anatomy Anthology, was influenced by a jaunt H.P. Lovecraft took with Sam Loveman, alleged binder of a book in human skin (and other sources indicate that the trip to the Flatbush cemetery happened with someone other than Loveman so read this with a grain of salt). Loveman and Lovecraft took a tour of a graveyard in a church in Flatbush that inspired Lovecraft’s story of grave robbers in “The Hound 9.”

Please bear with me as I engage in some pedantry. The MA article indicates the Necronomicon was bound in human skin and was the skin-bound tome mentioned in “The Hound.” That’s not the case. The book doesn’t actually appear in “The Hound.” Rather, it is mentioned, as the grave robbers discover an amulet around a corpse’s neck that was mentioned in the Necronomicon. The book bound in skin mentioned in “The Hound” is wholly different from the Necronomicon. I sense people may be ready to argue this point with me but here is the exact verbiage about the book bound in skin in “The Hound”:

A locked portfolio, bound in tanned human skin, held certain unknown and unnameable drawings which it was rumoured Goya had perpetrated but dared not acknowledge.

Yeah, I can’t find any evidence that Lovecraft’s Necronomicon, in any of the editions he discusses, was ever bound in human skin. I think the belief that this fictional book is bound in human skin comes from the Evil Dead films and a garbled belief that the book bound in human skin mentioned in “The Hound” refers to the Necronomicon rather than the portfolio of potential Goya drawings.

Speaking of the Evil Dead films, they are excellent examples of books bound in human skin being used in pop culture. Sam Raimi was undoubtedly influenced by Lovecraft, what with the book causing all the trouble being called the Necronomicon Ex-Mortis or Naturom Demonto. Raimi’s Necronomicon was bound in human skin, the words written in human blood, and if you speak the words out loud you will cause a house full of young people in a cabin in Tennessee to collectively lose their shit. The pop culture tendrils from Lovecraft and Evil Dead are long and intertwined and to elaborate on them would necessitate an entry just devoted to the way Lovecraft’s Book of the Dead has been used in all sorts of media, from film to music to comic books. Maybe that will happen here one day but until then, just know that Lovecraft’s Necronomicon was not bound in skin, but Sam Raimi’s was, and that the skin-bound book in “The Hound” was a collection of dark drawings.

Chuck Palahniuk’s Lullaby features a book bound in human skin. A reporter by the name of Carl Streator is tasked with writing about a rash of SIDS (sudden infant death syndrome) cases and discovers that the deaths are linked to a book called Poems and Rhymes Around the World. When the poems in the book are read aloud, the child who hears them dies – the book is referred to as a “culling” book. This was the last book of Palahniuk’s I really enjoyed without reservation and I think that the back story to this novel – Palahniuk’s reason for writing the book – is far more notable than the presence of a skin-bound killing book. Have a read – it’s horrible and far more disturbing than using the skin of the dead.

There are many elements of pop culture that involve books bound in skin – the film The Pillow Book, Mayhem’s first studio album

, among them – but I think those may need to wait for another time. Please feel free to share any examples of anthropodermic bibliopegy in pop culture that feel important enough to mention.

And if you were to be flayed and your skin used to bind a book, what book would it be? It’s a ridiculous and morbid question but one that is almost unavoidable after reading so much on the topic. Mr OTC would want to be used to bind the collected works of Patrick O’Brien. I would want to be used to bind books from the Burns Archive, especially any collection of death photography, like the Sleeping Beauty

books.

So this is what happens when I fall down a deep rabbit hole and write about what I find when I reach the bottom. I have no idea if this article will serve anyone other than me but it was enjoyable to write and I hope someone somewhere breathes easier knowing the more famous examples of anthropodermic bibliopegy are finally, at long last, in one place on one blog.

Online Resources

The Atlantic.com, “It Was Once ‘Somewhat Common to Bind Books with Human Skin.”

Atlas Obscura, “The True Practice of Binding Books in Human Skin.”

BBC.com, “The macabre world of books bound in human skin.”

Boston Athenaeum Digital Collections, “Narrative of the Life of James Allen, alias George Walton, alias Jonas Pierce, alias James H. York, alias Burley Grove, the highwayman: being his death-bed confession, to the Warden of Massachusetts State Prison.”

Burkeandhare.com, a site devote to the crimes of body-snatchers, Burke and Hare.

The Chirurgeon’s Apprentice, “Books of Human Flesh: The History Behind Anthropodermic Bibliopegy.”

Cleveland Magazine.com, “The Macabre Koran Revisited.”

The Daily Pennsylvanian.com, “Classic Texts – In the Flesh.”

DavidDarling.info/Encyclopedia of Science, “Flammarion, (Nicolas) Camille, (1842-1925).”

Et Seq/The Harvard Law School Library Blog, “852 RARE: Old Books, New Technologies, and the “Human Skin” Book at HLS.”

Fugitive Leaves, blog from The Historical Medical Library of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, “The Skin She Lived In: Anthropodermic Books in the Historical Medical Library.”

Georgian Gentleman, “The sad case of John Horwood, who took 190 years to be buried.”

The Grolier Club Website’s Item Details for Le Traicte de Peyne

The Guardian.com, “Flesh-crawling page-turners: the books bound in human skin.” (Note that the introductory picture has a caption stating that the book Des destinées de l’ame was proved to be bound in sheepskin – this is inaccurate and the text in the article disproves this erroneous caption, for it was Practicarum quaestionum circa leges regias Hispaniae/Jonas Wright book proven to be sheepskin. Evidently many people interested in the topic have contacted The Guardian online regarding this and they have not changed it. )

The Harvard Law Record, “Books Bound in Human Skin; Lampshade Myth?”

The History Blog, “Milton’s Poems Bound in Murderer Skin on Display.”

Houghton Library Blog, “Bound in Human Skin.”

i09.com, “Anthropodermic Bibliopegy; Or the Truth About Books Bound in Human Skin.”

Journal of American Medical Association: Dermatology, “Anthropodermic Bibliopegy: Lessons From a Different Sort of Dermatologic Text.”

Juniata.edu, “Sheepish: Juniata Tests Book Purported to be Bound in Human Skin.”

Literary Curiosities, “Odd Volumes.”

Medical Antiques.com, “Joseph Leidy, M.D.”

Mental Floss.com, “The Bizarre Art of Binding Books in Human Skin.”

Mental Floss.com, “The Quest to Discover the World’s Books Bound in Human Skin.”

Murderpedia.com entry for William Corder.

National Center for Biotechnology Information, “Acromegalic gigantism, physicians and body snatching. Past or present?”

National Center for Biotechnology Information, “Tanned Human Skin.”

Newberry.com, “Time Traveler’s Wife – Frequently Asked Questions about Audrey Niffenegger’s The Time Traveler’s Wife.”

The New York Times/ArtsBeat, “A Book Bound in Human Skin? Sorry, Not This Time.”

Original Skin: Exploring the Marvels of the Human Hide by Maryrose Cuskelly, Google Books e-book page scan for pagee 165.

The Typographic Hub, “Print’s Macabre Side.”

University of Kansas Medical Center’s Library’s Item Detail Page for Exercitatio antatomica de glandula pituitaria/Book bound in skin of circus giant

Wellcome Library item details for De integritatis & corruptionis virginum notis

Wikipedia entry for Lullaby by Chuck Palahniuk.

Wikipedia entry for Peptide Mass Fingerprinting.

Footnotes

- Smith, Daniel K. “Books Bound in Skin: A Survey of Examples of Anthropodermic Bibliopegy.” Eds. Joanna Ebenstein and Colin Dickey The Morbid Anatomy Anthology. Morbid Anatomy Press, 2014. 386-387. ↩

- Bogdan, Robert. Freak Show. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988. 275. ↩

- Smith, Daniel K. “Books Bound in Skin: A Survey of Examples of Anthropodermic Bibliopegy.” Eds. Joanna Ebenstein and Colin Dickey The Morbid Anatomy Anthology. Morbid Anatomy Press, 2014. 389. ↩

- ibid., 393. ↩

- ibid., 390. ↩

- ibid., 392. ↩

- ibid., 392. ↩

- ibid., 380. ↩

- ibid., 393. ↩

Fascinating piece! And I no longer require breakfast so thanks for that.

The idea of books bound in human skin is definitely, well, skin-crawling, but I don’t know why this is repellent to me when I’m not bothered in the least by human skeletons. Maybe because with bones there’s a literal and figurative remove from what we recognize as human? Gore in horror and real life is disturbing because it’s a perversion of the human form, and what is more grotesque than to turn part of a human being into, not even a relic or art piece but a functional object like a book cover.

One of my favorite DVDs from back when I still owned DVDs was a special edition of one of the Evil Dead movies that had a “Necronomicon” case with rubbery “skin.” I loved it but it was extremely creepy to touch. Brrr.

I don’t have any stories of anthropodermic bibliopegy to share, but do you recall a rumor (or a true story?) that went around when Poppy Z. Brite’s Exquisite Corpse came out, that there had been a warehouse fire resulting in one or more fatalities, and the first printing of that book was imbued with smoke from burnt humans? It’s been a while so I’m no longer clear on the details and I can’t find any reference to it online.

As for what book I’d want my skin used to bind, I think it would be cool to be made into Moleskine notebooks like the one you mentioned. I like to be useful!

This was a great essay. I’d seen maybe one of these articles before. It’s nice seeing this topic so comprehensively.

The book I’d want my skin to bind was one I had to think about and I’m still not sure. I considered a Bible as a gift for my family, but I’m pretty sure they wouldn’t want that. The other ones I considered were NAKED LUNCH, THE TORTURE GARDEN, INVISIBLE CITIES and a Library Series style collection of Hubert Selby Jr.’s novels.

I have a book owned by Glen Adam’s of the year galleon press before he died. He published the book and sold it to me. I’d like to get it tested. I’ve been waiting 25 yrs.