Book: Sleeping Beauty III, Memorial Photography: The Children

Author: From the Stanley Burns Archive

Type of Book: Non-fiction, photography, death photography, funerary customs

Why Do I Consider This Book Odd: Pictures of dead children will always be a bit odd.

Availability: Released by The Burns Archive in 2011, you can get a copy on Amazon here:

But I would strongly recommend that anyone interested in the macabre photography from the Burns Archive go directly to them. Sometimes you can get the books far cheaper if you buy directly from the press itself. Not always, but compare before you buy. As much as I like the kickbacks I get when y’all buy stuff using my Amazon Affiliate link, sometimes one can get a new Burns Archive book for literally hundreds less on the Burns Archive site than buying it from a third party vendor on other book sites.

Comments: I’d intended to discuss this book long ago but I put it up on display with a piece of art that Mr. Oddbooks bought me. Once something is on a stand behind glass, I am loathe to mess with it too much. However, I recently started using some software to analyze the traffic to this site and noticed a lot of traffic coming from searches about death photography. Then, shockingly, I noticed some hits coming from Pintrest. You know, the site wherein people share pictures of cake, high heels and celebrities with cats. Never thought death photography would be an interest on such a fluffy site, and for some reason, discovering that fact encouraged me to get my book off the stand and discuss it. Actually, I have several Burns Archive books on creepy topics that I should discuss here.

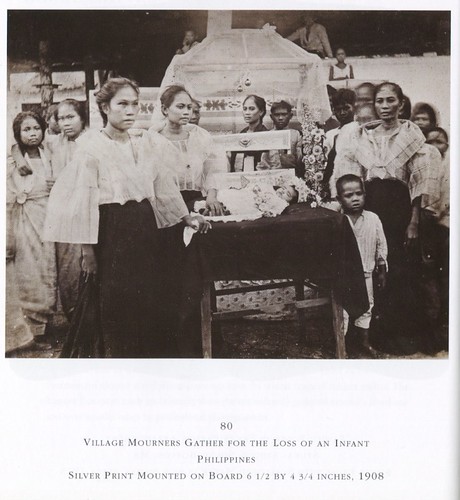

For now, I’m going to discuss Sleeping Beauty III. This book is much smaller in size than Sleeping Beauty I and II, almost appropriately because this volume deals with children exclusively. Sleeping Beauty III has 125 pictures from the 1840s to present time, and spans several cultures. Though the book is definitely Western-centric, and truly most death photography is of white people, this book contains some pictures from other cultures.

A lot of people find memorial photography morbid – if you stumble across a Facebook account where death photography is discussed or reproduced, the comments range from an appreciation of the history to people thinking the parents long ago were insane or that the whole thing in general is somehow morally wrong or gross. “Ewww! Why would anyone want to take a picture of a dead person?” As much as I dislike it when people react to these pictures from a strictly modern sensibility or a squeamish quasi-morality, I often have a hard time explaining why it is such images appeal to me. Burns does his best to explain why these images may seem so jarring:

It is difficult for most of us today to understand the prior culture’s need to take memorial photographs. We no longer live with personal death and dying as part of our everyday lives. By the 1930s, dealing with death had been left to professionals ranging from physicians to morticians. The advance of medicine, control of killer epidemics, the ability to treat disease, and the removal of the sick from the home made us unaccustomed to living with and seeing death. Children dying before parents, something so common in the nineteenth century, has become unusual in the twentieth century.

He goes on:

Memorial postmortem photographs have deep meaning for mourners. These keepsakes become special icons that help survivors move through the bereavement process. Healthy grieving ultimately distances us from the dead. The human bond, our connection with others, is mankind’s strongest guiding emotion and thus influences our fears and actions. These images represent confrontation with our loved one’s mortality and our own.

I would like to think this fear of death that these images can provoke is behind the “Yuck!” reactions people sometimes express.

I often have a hard time discussing death photography because I relate to these images on an emotional level. While the appeal of the Burns Archive collection tends towards the visceral response, Burns offers useful information in the book to give context and history behind the photographs. I find the best way to discuss this little book is to reproduce a few pictures from it and quote the information that Burns provides to help us put these pictures into an historical context.

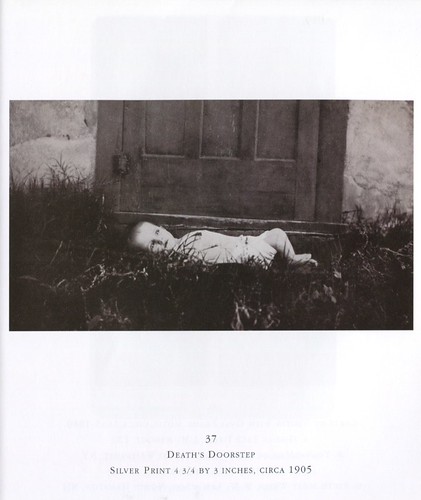

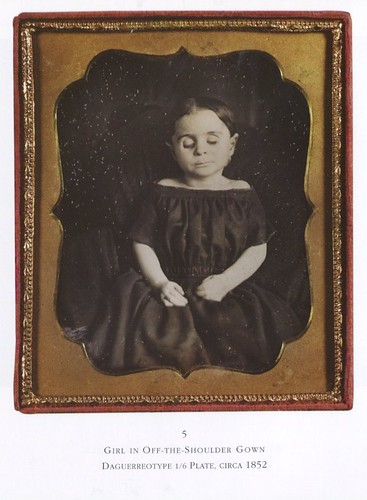

Reading postmortem photography comes with understanding the culture of death in a given era. Today it is traditional to close the eyes of the dead. But in the past, when a memorial photograph was taken, families frequently requested, especially for children, that the eyes be open. This was particularly the case for children who had never been photographed when they were alive. A second, eyes-closed photograph with changed pose would signal the memorial photograph. Photographs that depict the dead child in some sort of activity as if alive are considered “posthumous mourning portraits.”

This picture is haunting. It looks to me like his eyes may have been painted on the print to make them look open. The symbolism of this little boy at death’s door really isn’t symbolism. He’s dead and gone, and his eyes don’t give this picture any ambiguity.

Photographing the dead with eyes closed is testimony to the acceptance of death. Keeping the eyes open seems to be an attempt to keep death at bay, to deny the undeniable. They reveal the heartbreaking pain of families fighting to keep the the dead alive for one more image. In some cases the child is surrounded with toys or other objects to show his favorite possessions.

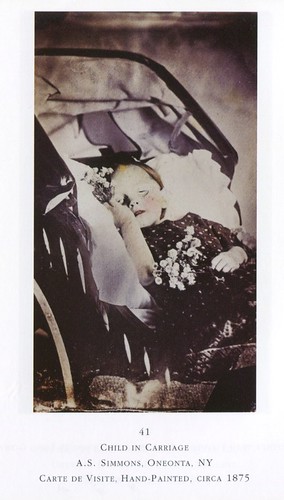

This little girl in her carriage had her eyes open but she’s clearly dead. This is how so many of the children with their eyes open appear – even if the parents wanted pictures to show the child as if alive, the results to a modern eye seldom conveyed life.

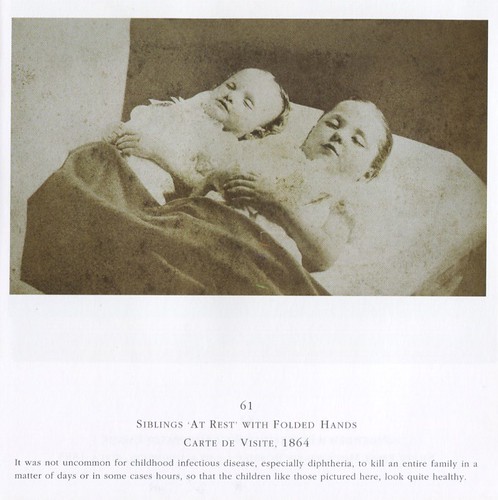

We can observe something quite curious from this time: with the exception of children who died from dehydration or from viruses that left conspicuous skin rashes and adults who succumbed to extreme old age or deforming cancers, the dead would often appear to be quite healthy. Ironically, because of modern methods for sustaining life, contemporary corpses don’t look nearly as robust as the remains of our ancestors.

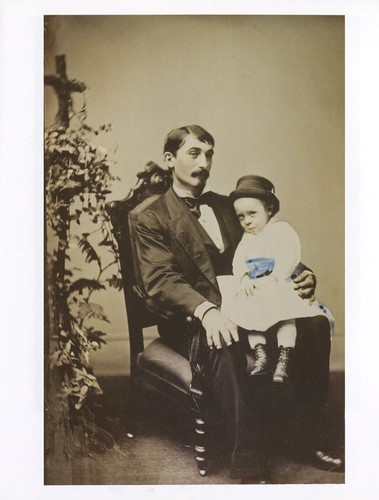

This little boy actually does look very much like he is alive and is just unhappy at being photographed. His father’s expression doesn’t give us any real clue that this is a memorial photograph. In a sense, all of that makes this picture all the creepier.

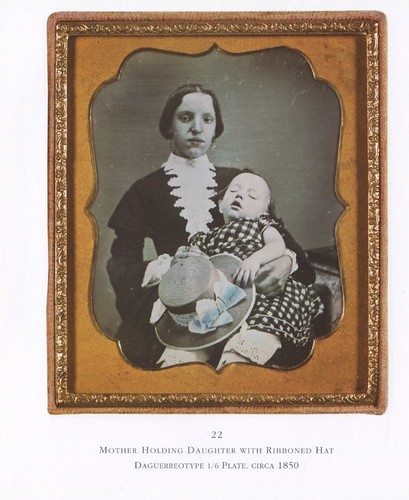

This picture is a bit more ambiguous. There are signs that this is not a happy photograph – the mother’s expression, who would have paid money back then for a professional photo of a sleeping baby? But the child, even with eyes closed, seems healthy.

The industrialization of the early nineteenth century drove the rural populace into cities and transformed them into overcrowded slums and factory towns: a fertile breeding ground for infectious disease. Along with epidemics of cholera, yellow fever, and small pox, childhood diseases devastated the country. Diphtheria, scarlet fever, measles and mumps spread rapidly and killed quickly. In a matter of days, a family and occasionally an entire village could lose all its children.

And as observed above, these children don’t show the horror of the illness that killed them on their bodies. They really do look like they are sleeping.

Of all the subjects in memorial photographs, images of children are the most common. Parents desperately wanted to preserve the lives and existence of their cherished loved ones. Often the memorial photograph was the only picture of the child. In contrast to memorial photographs of adults, memorial photos of children often emphasized the facial features, creating an increased feeling of intimacy.

This little girl looks like she may have suffered a while before she died but she is a perfect embodiment of the intimate look at the child in an attempt to record her features.

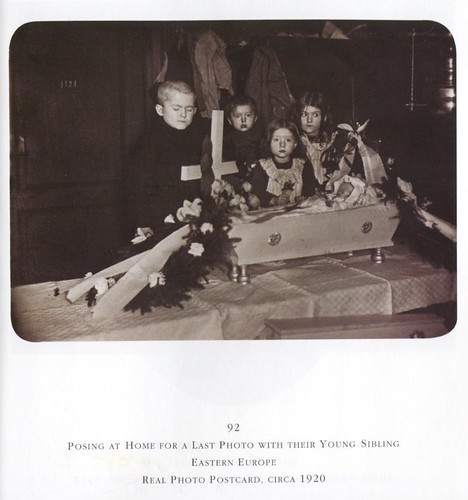

In the United States professional postmortem photography ended by the 1930s. In European, Latin American and other cultures it remained an active part of the bereavement process until the late 20th century. It was particularly popular in Eastern Europe…

This photograph, for whatever reason, is the one that haunts me the most. I think it’s the somberness of the photo – the little casket laid upon a cloth on a table, the wreath, the siblings posing for the last time – with the obvious signs of everyday life in the background. Note the coats upon hooks hanging over their heads, the door with their apartment number. It’s quite sobering to have death so close in the midst of every day life.

This picture is notable not only because it is from the Philippines but mainly because of the expression on the face of the woman closest to the camera. We often see in these photographs a sort of solemn grace but it is not often we see a person clearly fighting back open sorrow. Several of the women have very sad demeanors. When I contrast them to most of the Caucausian adults featured in this book, their sorrow is almost refreshing. I am from stoic stock myself, for the most part, and there’s something about a stoic face when a child has died that makes the observer feel like death was so common that perhaps parents were less affected than we would be now. That’s untrue, of course, but it’s just how I feel as I look at these pictures.

During the past two decades memorial photography has had an increasingly significant place in children’s hospitals and in grief and bereavement programs… Whatever the artistic or personal sensibilities of the bereaved, it is our hope that this series will help those who have lost a loved one to use photography to honor the lives of their children, however short, and to help overcome their grief.

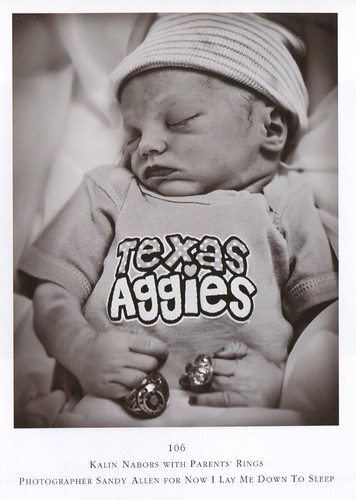

When I first read the above quote, I wondered what Burns meant, as most memorial photography, even as it varies, follows certain markers of decorum. This baby’s death photograph almost has a light-hearted joviality to it that gives no quarter to ideas of gravitas. Her parents’ college rings, the Aggie gear, painted nails… But death is so very personal, and humor can so often be married to affection and love. This is not one of my favorite photographs but it’s got a lot in common with the photographs that were so deeply personal that they needed no explanation. One cannot look at this picture and not see that it is deeply personal in spite of being so deeply affected, and that there is the same story behind it: all the plans the parents had for their little girl are gone.

That’s what this collection is. That’s the heart of this book. The loss of hope for a future even as parents tried to keep some memory of their lost child in the present. It’s really quite something when a book of photographs conveys such a specific emotion. Since this book is still in the affordable range on Amazon and at the Burns Archive, I highly recommend that people who enjoy this sort of emotional challenge get a copy of this book sooner than later.

all pictures in this entry are copyright © of the Burns Archive

I admit I do find photographs like this disturbing. For me it’s part of a wider discomfort/ambivalence I feel towards treating the corpses of dead people as if they’re still that person. Like in movies, for instance, when someone dies and their loved one speaks to them or kisses them — something about this disturbs me. Whether it’s dead pets or family members that I have been present at the deaths of, I feel repulsed by their corpses because they visibly lose the animating spirit that made them who they were, and what’s left seems almost like a grotesque parody of that former person — as if the person has been taken away and replaced with an effigy, that resembles them just enough to be creepy in that “Uncanny Valley” way.

It’s odd, but I found that last photo the most unsettling of all of them, because of the “Texas Aggies” t-shirt. My initial response upon seeing it, before further comprehension set in, was shock that the dead baby had been decorated with some kind of advertisement. It’s one I have to think about in context in order to find its emotional center. If I think about it I can see what the parents were probably trying to do, but at first glance I just see a peculiar, morbid imposition upon the corpse that verges on blasphemy. It’s confusing to me because in some circumstances — like in movies or news stories about serial killers — we’re shocked and horrified if the killer arranges or poses his victims’ bodies. In that context, the desire to “animate” the dead seems grotesque and perverse. Yet in other contexts it’s OK (like when people praise the lifelike quality of a well-embalmed corpse).

I found the Aggie picture appalling the first time I saw it for much the same reasons you did. But as I deconstructed the picture, what I loathed as a lack of dignity or strange advertisement became signposts of loss. Those parents would never see their little girl become an A&M legacy. They would never see her graduate from high school. The mother would never get to experience rites of passage as she helped her daughter learn to paint her nails and grow into a woman.

I should scan it and put it in this comment section so you can see it, but in Sleeping Beauty I there is a picture of a boy named Charley. Charley was a toddler when he died and his parents posed him with the items he loved. If I recall correctly there was a wagon and a small train. Kalin didn’t live long enough to have her own toys, her own items associated with her and her parents were forced to adorn her with their lost dreams. Had she lived as long as Charley, I think her picture would have been far different.

I think sometimes that deconstructing these pictures is the main reason why I am drawn to death photography.

Good point — the infant hasn’t lived long enough to be anything but a blank canvas that the parents project their hopes and dreams for that child upon. Not even a distinct personality yet. Although I can’t not be creeped out by these photos, I agree that it’s interesting to deconstruct and interpret the deeper meanings and motivations behind them.

I came across your review and comments while updating Sandy Allen’s professional studio website. She is the photographer of the “Texas Aggies” photo. I’m her husband, and thought you should know Sandy is not only a professional maternity and newborn photographer, but is also the area coordinator for Now I Lay Me Down To Sleep (NILMDTS), a completely volunteer organization of professional photographers who provide the gift of professional bereavement photography to families suffering infant loss. This is one of those free professional photos provided to the family.

R. Stanley R. Burns was extremely generous reaching out to NILMDTS for photos reflecting modern practice – and Sandy was one of the photographers whose work he graciously included in the reference.

This modern version has become very comforting to families – Sandy has personally provided this service for free to over 100 families, and trained and assisted dozens of volunteers here in the Austin area who provide this service almost every week. Nationwide, NILMDTS provides this service to families for free every day.

The story of the Texas Aggies photo belongs to the loving family that requested it – I certainly can’t share it. But I am immensely proud of the work Sandy and hundreds of others at NILMDTS.

You can find out more about Now I Lay Me Down To Sleep at nilmdts.org

Phillip, thanks so much for this comment. As a fellow Austinite (well, I’m in Pflugerville), I want to share the link to Sandy Allen’s maternity photography website in case any local readers need such services: https://momentsfromtheheart.com/

The Aggie photo was laden with meanings the modern mind may have a hard time understanding at first. I initially really didn’t like it until I studied it and understood it. I think I want such photography to be somber and sad and this photo is definitely sad but still had a buoyancy that seemed discordant until I understood what all the signposts in the photo indicated – lost dreams, lost future.

I also commend your wife for taking these photographs and the families for being willing to share something so personal. NILMDTS offers a service that it is heartbreaking to consider, and your wife is remarkable for ensuring that grieving families can have these memories. Thanks again for sharing this information.